Haunting, History, The Medium

Christian Haines, Managing Editor

Warning: This article spoils much of The Medium’s plot and gameplay.

The Medium (Bloober Team) is a game mired in history. The game wrestles with the specters of communism and fascism in a historical moment – the post-Cold War period – when those social movements are supposedly dusty relics. Of course, if you’ve been paying attention to current events in Poland, where The Medium was developed, you’re probably already suspicious of descriptions of history as uninterrupted social progress. Poland has seen the rise of a right-wing populism that’s defended Holocaust denialism, propagated Islamophobia, banned abortion, and tolerated neo-Nazi thugs. It’s not unlike the United States or other parts of Europe in this respect.

The Medium using photographs to give its historical references a documentary air.

The sins of history haunt the present, and horror has long been a genre devoted to channeling the specters of the past. As its title suggests, The Medium is a game about ghosts. The protagonist, Marianne, communicates with the dead. Much of the game revolves around bringing peace to troubled souls, freeing them from the buildings they’re compelled to haunt. In gameplay terms, these kindly exorcisms usually take the form of simple puzzles where you fetch an object thematically-linked to the character in some manner. In the first of these instances, Marianne searches for a tie and tie clip belonging to her adoptive father, Jack. Although it’s through conversation that Marianne ushers Jack into whatever comes next, it is only after combining the tie and tie clip in the inventory menu that the game progresses. It’s as if by putting things back in their proper place, you were settling the present, ridding it of contamination from the past and stepping into the possibility of some brighter future. But the ghosts keep coming.

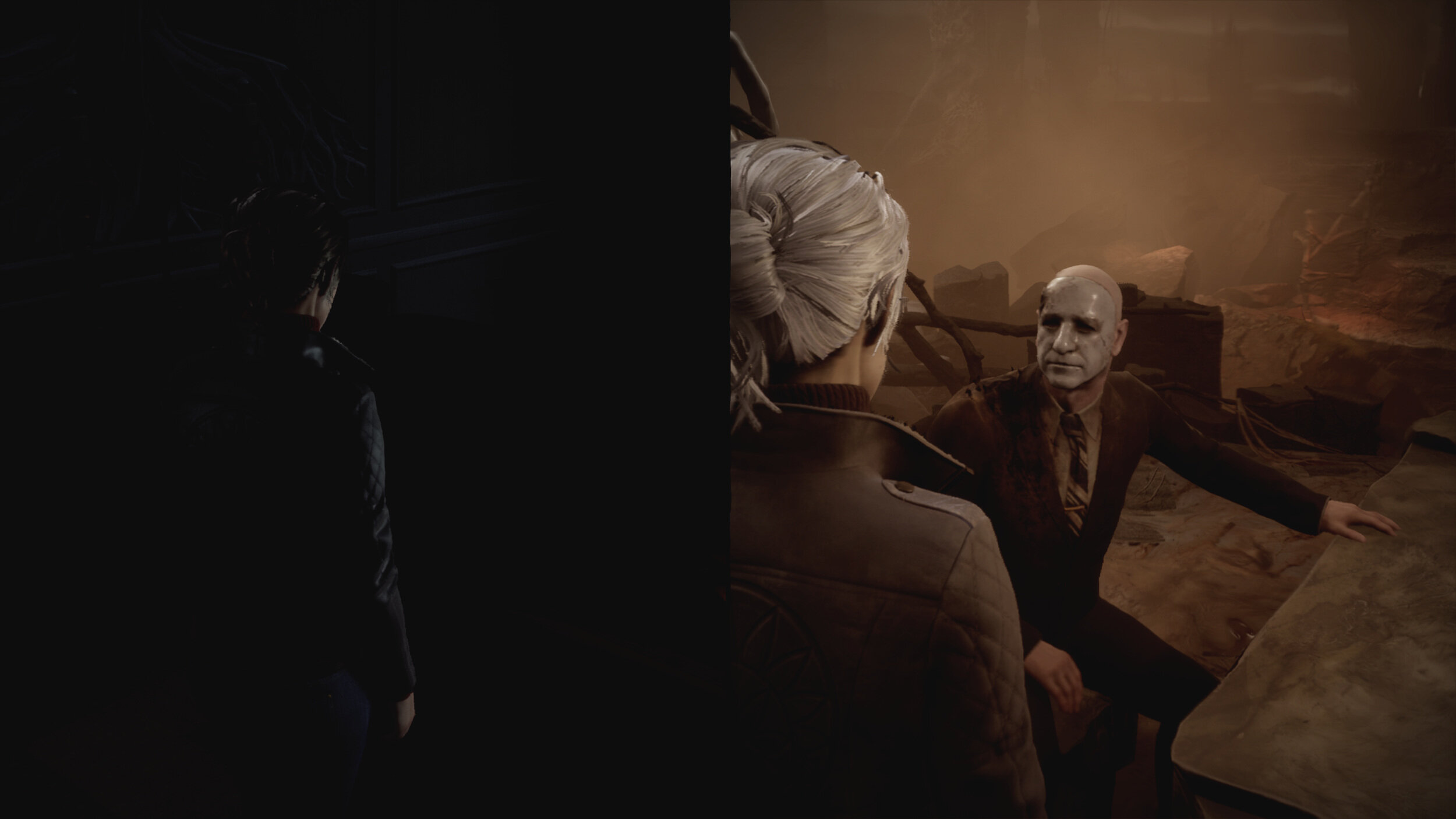

Marianne releases her adoptive father from the limbo of the spirit realm.

The game translates Marianne’s role as a medium into visual spectacle by presenting the physical world and the spirit world simultaneously. On one side of the screen, Marianne moves through the banal scene of a summer camp for working class families – the central setting of the game is the Niwa Workers’ Resort, a resort funded by the communist-era Polish government. On the other side of the screen, one sees the same scene, but warped into a phantasmagoria of decaying vegetation, doors made of flesh, strange stone sculptures, ethereal moths, and spirits that resemble walking corpses.

Niwa, a communist workers’ resort falls into ruin.

Bloober Team’s “dual-reality gameplay” gives tangible form to the idea that the present is always haunted by the past, that history is never really over because it lurks in the background of everyday life. The more interesting puzzles in the game involve seeing how actions in one reality affect the other reality. At one point in the game, for example, turning the hands of a clock in the physical world transforms the room housing the clock, but only in the spirit realm. As the hands turns on one side of the screen, the specters on the other side of the screen flit about in an echo of their daily routines. It’s a fitting commentary on the way that for all of their mechanical precision, clocks also allude to weird remembrances and buried secrets.

A puzzle in which the hands of the clock conjure the ghosts of the past.

As interesting as its dual-reality puzzles may be, The Medium is a mess when it comes to history. It’s overstuffed with historical detail and jumbled in terms of how it puts those details together. There are plenty of lore documents to be found in Niwa, postcards, photographs, and hand-written letters. They evoke the setting as a site of history mostly by alluding to the traumas of individuals who have passed through Niwa. Like a lot of horror fiction, the game has a pronounced tendency to confuse salacious content with the stuff of genuine fear. The game handles sexual assault, child abuse, anti-Semitism, and genocide in a clumsy fashion; they’re more means to create a spooky atmosphere than complex matters approached with care. One of the more compelling scenes, at least in terms of artistic splendor, features a beautiful garden maze. It tells the story of a childhood friendship between a young boy and a young Jewish girl during the WWII German occupation of Poland. The game ends up transforming the boy’s inability to save the girl from fascist forces into motivation for his adult crimes of sexually abusing another young girl (Marianne’s sister).

The spirit realm is all beauty, decay, foliage, and ferns.

That the game doesn’t really know how to bring this disparate and difficult material together in a coherent fashion becomes even more obvious when it introduces the Maw, a monster that serves as a repository for all the suffering implicit in the human condition. There are several instances in which you have to sneak by or outrun the Maw. These scenes serve to transition the player from one central location in the game to another, but they’re also a distraction – a device for collapsing the very different kinds of horror to which the game alludes into a general concept of evil. In this context, monstrosity isn’t just shorthand for historical evils, it’s a short-cut. It avoids the kind of thoughtful historical reflection that might make sense of the respective legacies of fascism and communism in favor of sensationalism.

Monster! Maw! History is a nightmare on the brain of the living that chases you down hallways.

The Medium’s historical messiness is more than a misstep on the part of Bloober Team, however. It speaks to a more general cultural condition, what the Marxist critic Fredric Jameson once referred to as “the waning of our historicity, of our lived possibility of experiencing history in some active way.” Jameson wrote this almost 30 years ago in an account of postmodernism (“the cultural logic of late capitalism”), but he was describing the logical conclusion of a more general tendency under capitalism. Capitalism puts history – every object, every person, and the traces they leave behind – in service of producing new commodities. It’s not just that we’re defined by the things we work on and consume but also that these things become more and more ephemeral, more and more abstract. Like ghosts, or memes. One of the ways Jameson tries to get at this condition is by analyzing “nostalgia films.” These are films like Chinatown and American Graffiti that evoke the past not through the nuanced representation of history but through “stylistic connotation”: the use of supposedly accurate fashions, car makes, or manners of speech, whose purpose isn’t to comprehend history but to create a feeling of “past-ness.” We find ourselves, Jameson writes, in “a new and original historical situation in which we are condemned to seek History by way of our own pop images and simulacra of that history, which itself remains forever out of reach.”

Jameson’s critique of postmodernism isn’t meant to condemn a particular cultural style or trend. He’s arguing that this weakening of historical consciousness is a shared condition of contemporary cultural production (video games included!). Which is also to say that if Bloober Team has produced a game that’s rich in historical trivia but poor in historical understanding, it’s not simply the studio’s failure. It’s also a symptom of the general difficulty of imagining history in the present, especially when it comes to large-scale political movements and radically different social systems. You see this difficulty in the way that The Medium collapses together the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, treating them as if they were identical.

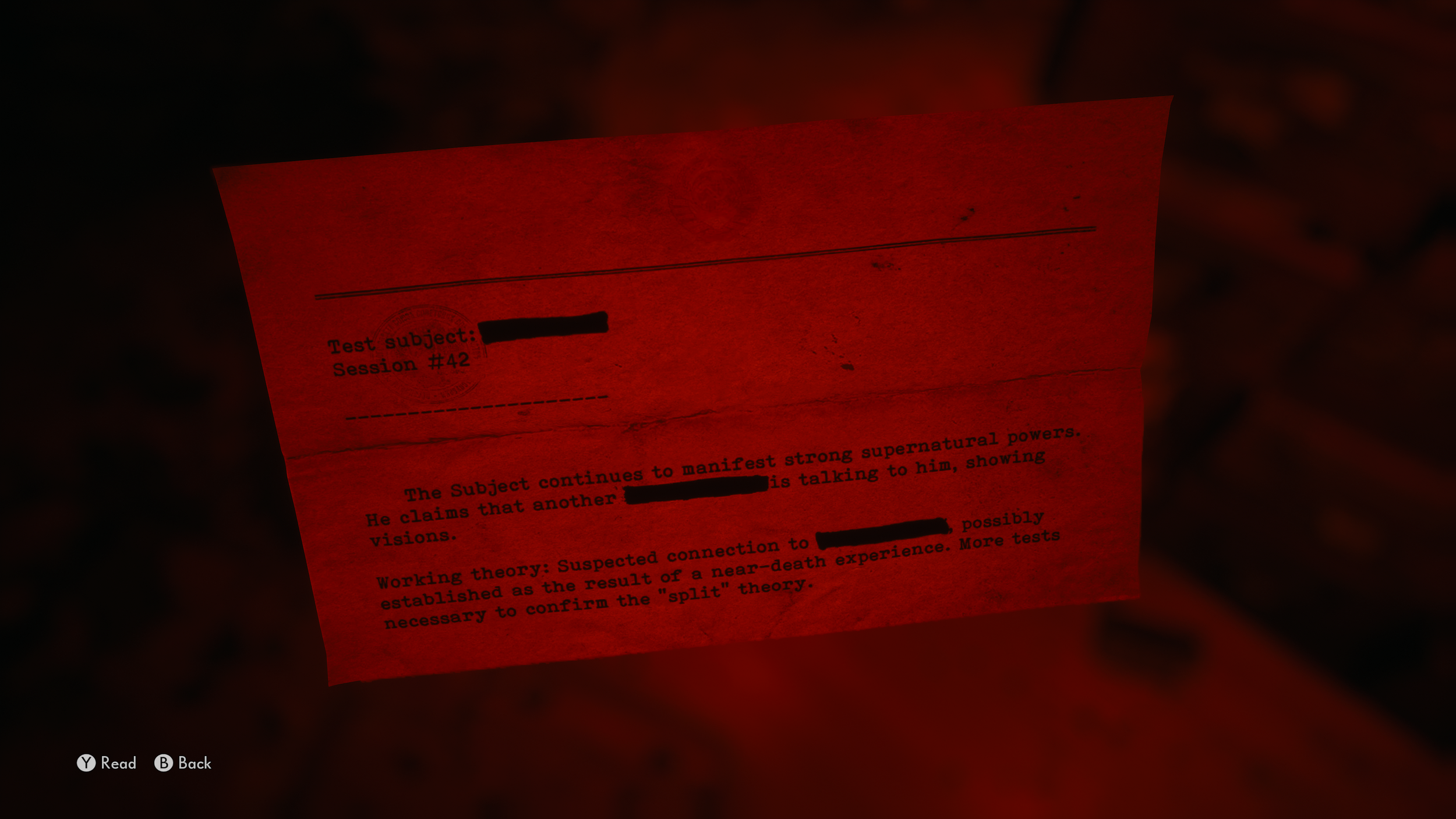

Top-secret supernatural historical documents.

Marianne’s father, Thomas, is the source of her supernatural abilities as a medium, and his powers come from being experimented on by both Nazi and Soviet scientists. The game positions Marianne and her family as individuals struggling against the overwhelming and homogenizing force of mass politics. This is especially obvious when, playing as Thomas for a short section of the game, you enter the unconscious of an agent of the Polish secret police. The level design in that sequence consists of columns and columns of file cabinets, as if his mind has been completely consumed by the bureaucratic machinations of Polish communism.

A mind consumed by bureaucracy - history’s really just a never-ending pile of paperwork.

It’s tempting to interpret The Medium as an exorcism of Poland’s past. Bloober Team seems to be wondering what it would be like to finally have done with the historical legacies of fascism and communism, to truly live after what Francis Fukuyama called “the end of history”: a neoliberal dreamscape in which we really are only individuals and families and in which political movements and social classes are only vestigial organs – the useless remains of a barbaric past.

But what if the opposite is true? Could The Medium actually be expressing a longing for history? In an essay on Kubrick’s film version of The Shining, Jameson writes that “the nostalgia of The Shining, the longing for collectivity, takes the peculiar form of an obsession with the last period in which class consciousness is out in the open: even the motif of the manservant or valet expresses the desire for a vanished social hierarchy, which can no longer be gratified in the spurious multinational atmosphere in which Jack Nicholson is hired for a mere odd job by faceless organization men.” Jameson’s point is that the tendency of horror films to divide reality into Good versus Evil, Present versus the Past, the Family and the Other, stems from a deep desire for the kind of community that global capitalism typically destroys. It’s more comforting to face monsters and ghosts than to accept the sheer indifference of corporate capitalism.

Remnants of a moment when worker solidarity and pleasure were intertwined.

From this perspective, The Medium’s setting – Niwa, a communist-era working class resort – isn’t a coincidence. The crumbling walls represent a lost sense of social solidarity, a forgotten time when pleasure and collectivity were closely intertwined. For all that the game represents Marianne as a unique individual with special powers, it also shows her searching out community in the wreckage of history. The game’s narrative structure and level design are organized around overcoming isolation: it’s not just that the game turns out to be a quest to find your long lost sister, after you’ve lost your adoptive father, it’s also that the whole game involves reuniting objects with their proper places, people with their pasts, and social settings with their histories.

The Medium stumbles over its historical material, confusing social problems from the past with metaphysical Evil. It indulges in lust for salacious content as if genre conventions were an excuse for carelessness. But the game’s an interesting failure, and not just because of its compelling visual style. It exposes a defining paradox of our moment in time, that we long for history and community, that we’re searching for something larger than the family or the individual, but that we find it difficult to imagine the objects of our desire as anything other than ghosts or monsters.

Suggested Readings:

Read the intro to this series of articles, “History’s Arcades,” here.

Check out some of our other writing on horror games, including my piece on Dead Space 2, Christopher Breu on Resident Evil, and Don Everhart on Silent Hill.

Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991).

Fredric Jameson, “Historicism in The Shining,” collected in Signatures of the Visible (1992).

“Post Script” on The Medium in Edge #356 (April 2021), by Edwin Evans-Thirlwell.