History’s Arcades

Christopher Breu & Christian Haines, Editors

“Method of this project: I needn’t say anything. Merely show. I shall purloin no valuables, appropriate no ingenious formulations. But the rags, the refuse – these I will not inventory but allow, in the only way possible, to come into their own: by making use of [by playing!] them.” – Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project.

German Jewish cultural critic Walter Benjamin was working on his most ambitious book when he took his own life on the border between France and Spain. At the time, Benjamin felt his only choice was either to commit suicide or be forcibly returned to Nazi Germany by border control. The book he was writing was called The Arcades Project. It’s an unfinished 1,000+ page volume that stitches together quotations and commentary to capture a sense of the fantasy life of the nineteenth-century European middle-classes.

Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate, or Class War in London, or the one where you meet Marx.

In the book, Benjamin writes about the arcades, covered-shopping districts that existed in Paris during the nineteenth century. Benjamin studied the arcades and the various goods for sale in them as portals into the desires, fantasies, and beliefs of a class – the bourgeoisie – that had recently come into power with the rise of industrial capitalism. If the work of Karl Marx revealed the underside of capitalism, or the way capitalism relies on exploitation and violence, Benjamin, writing half a century later, wanted to understand how the consumer products available in Paris’s arcades represented a different dimension of capitalism. He wanted to decipher how shopping and commodity culture nurtured dreams, fantasies, and the uncanny. He was interested in the arcades as both a portal and a mirror—an opening into other worlds and a looking glass reflecting the self-conception of the middle-class.

Of course, a different understanding of arcade springs to mind these days. Instead of Benjamin’s covered shopping districts, we think of dark and mysterious, yet inviting, digital game palaces. These arcades feature machines with gaudy designs and bright colors, emblazoned with titles like Magic Sword, Street Fighter, and Carn Evil. Like the Parisian arcades of Benjamin’s book, video arcades are already a thing of the past (except when they get reinvented as part of retro-gaming bars and museums), but they’re still a mirror of and a portal to the fantasies, dreams, and desires that shaped the late twentieth-century gamer. They too represent what Benjamin describes as the “phantasmagoria” – the ghosts, the dreams, the hallucinations – of our culture.

Key art for Civilization VI, or history as collage.

Video games open doors to other worlds. They draw players into a space of fantasy. Often these fantasies are wholly fictional, presenting a world far different from our own (for example, the richly-detailed swords and sorcery realm of The Elder Scrolls) or a time that hasn’t come to pass yet but might (as in the cyborg-filled corporate dystopia of the Deus Ex series). But these portals also function as mirrors. Even when they are situated in entirely imaginary worlds, they tell us something about ourselves and our desires. This mixture of mirror and portal becomes even more pronounced when games actively engage the historical past, or when we think back on the history of gaming itself.

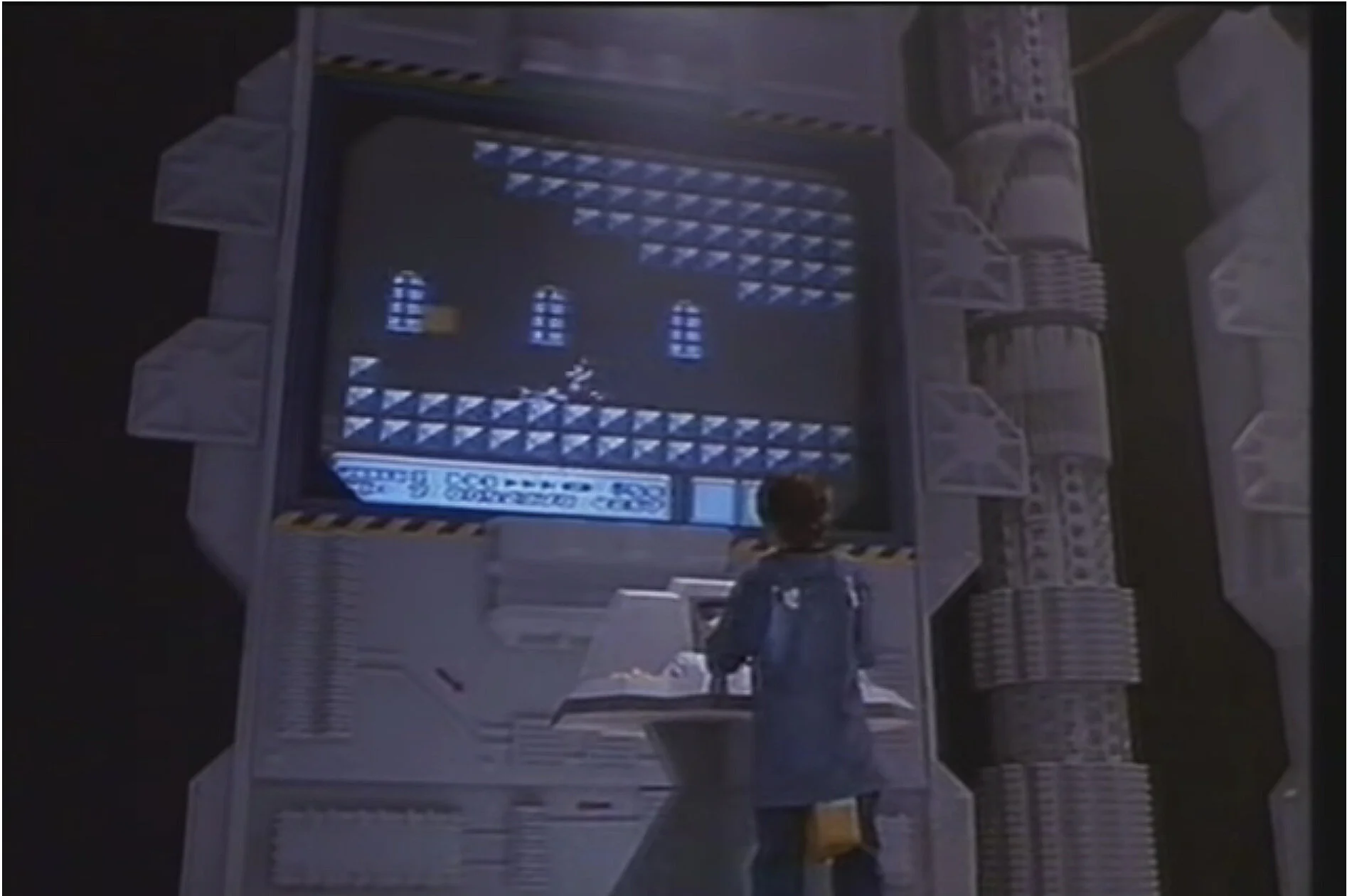

Still from The Wizard (1989), in which an arcade competition culminates with Super Mario Bros. 3.

Over the next several weeks, we will be publishing a series of articles looking at how video games play with history and how we play at telling the history of video games. Some of the questions we’re thinking about are: What kinds of histories do games tell? What happens when games represent historical turning points as exciting adventures? How do horror games grapple with the way the past haunts the present? What lessons does the lore in fantasy games hold for writing history in our actual world? What do post-apocalyptic games have to say about the historical qualities of the present? How do games tell the history of gaming through their gameplay mechanics? What would happen if we were to look at video game history from the perspective of the games that never got released? How does our understanding of video game history change when we center developers and gamers from marginalized communities?

Articles in the Series:

Christian Haines on history, haunting, horror, and communism in Bloober Team’s The Medium.

Christopher Breu on the Assassin’s Creed series, The History Channel, and conspiracy.

Nate Schmidt on Walden: A Game and how archives create history.

Don Everhart on how Moose Life reinvents the claasic arcade experience.

Roger Whitson on Kentucky Route Zero, haunted machines, and the Internet that never was.

An interview with Jesper Juul on the history of indie games.

Jason Mical on the Quest of Glory series, game preservation, and the fragility of video game history.