The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild: Playing Together During the Pandemic

by Patrick Jagoda and Kristen Schilt

Part 1: Freedom and Constraint

In March 2020, Chicago issued a stay at home order because of COVID-19 and we were cut off from our friends, family, and workplace. As the world around us shut down and transformed at a shockingly rapid pace, we loaded up the 2017 video game The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (BOTW) for the Nintendo Switch to use as a distraction. All we had now, once our remote workday ended, was time. For Patrick, this was a return to a beloved franchise, albeit one that had undergone immense upgrades since the last iteration. For Kristen, it was the first foray into not only a Zelda game, but also a large open world game. We began playing in March and, by May, we had logged 215 hours and defeated the final boss, Ganon.

Playing BOTW ended up being more than just a distraction from the pandemic: it became an opportunity to play together in a world that felt more claustrophobic by the day. Writing about games too often focuses on a game’s story or its mechanics, without taking seriously how people actually play games in practice. Play is never either a space of unrestricted utopian freedom or ideological algorithmic control. It is both and more. As we hope to show, in the context of a game, play can be seen as a way of thinking, learning, being, feeling, and creating together.

During the pandemic, BOTW offered a virtual freedom of movement that provided relief from the dual feelings of endless repetition and encroaching doom that seemed omnipresent. In BOTW, we could walk around freely, ride horses, teleport across locations, climb vast mountains, glide from great heights, and discover secrets at every turn. In no time at all, we could move from the aerial setting of Rito Village to the underwater coral gardens outside of Lurelin Village. We could revisit favorite settings — for instance, developing an affinity for the vegetable seller at Kakariko Village and conducting most of our trades with her. Other times, during exploration, we might stumble across a new puzzle-laden shrine, landscape, or character who might make the world feel even larger than before. The sense of familiarity was grounding while the surprise factor was a balm to the endless hours we spent working remotely via Zoom.

Link in Breath of the Wild (2017)

The feeling of freedom in BOTW, for us, came in response to a unique context and situation of the emergent pandemic. At the same time, it’s worth noting that “freedom” emerged as a buzzword among video game journalists and designers much earlier in the 1990s (during a period when parallel development such as the neoliberal “free market” were also flourishing). Beyond the freedom of choice sought across game genres, particularly with the rise of 3D games during this period, open world games began to offer increasing scales of freedom.

Technically, open world games can be traced back to tabletop roleplaying games such as Dungeons & Dragons (1974), text adventure games such as Colossal Cave Adventure (1976), and earlier video games such as the original The Legend of Zelda (1986). The 2000s raised the bar with games that included huge explorable spaces with opportunities for emergent gameplay that was improvised rather than being dependent on preset missions or linear progression. Grand Theft Auto III helped popularize the trend with a (relatively) massive open word. Other notable efforts include World of Warcraft (2004) and RPGs like The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim (2011). In 2016, No Man’s Sky upped the ante by offering a procedurally-generated universe containing 18 quintillion planets.

Link in his original adventure, The Legend of Zelda (1986).

The spatial and interactive freedom in BOTW is not necessarily original. In a negative sense, this genre taps into colonizing desires of discovery, adventure, and mastery. In a more promising sense, it promotes forms of experimentation, improvisation, and creativity that have more to do with exploring and complicating a piece of software. Encountering these varied affordances during the pandemic enabled an experience of freedom that we had not needed to this extent. At the same time, we understood that any pleasure or relief we felt in the game’s open spaces, which we now lacked in our everyday lives, existed in a tension with the game’s numerous instances of exoticism and ableism.

Alongside the sense of freedom, we curiously experienced and enjoyed its seeming opposite: constraint. To put it plainly, in BOTW you can finish things. The beginning of the game can be difficult. Weapons break easily and enemies are often far more powerful than you, yielding an existence that is, as the seventeenth-century political philosopher Thomas Hobbes would have it, “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” As you persist, you gain more hearts and stamina. You can venture places you could not before and win battles that seemed impossible before.

At times, life in BOTW may feel “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

In many ways, completing the endless side quests (well, not that endless because we did them all) or locating all of the 120 shrines became a substitute for the neoliberal hamster wheel of small tasks that structures a huge portion of our lives as professors. Our shared instinct to do well — to excel at everything we were asked to do — kicked in and it gave us, at least briefly and somewhat sheepishly, a feeling that we were accumulating accomplishments and moving up in a hierarchical system. Of course, this type of feeling isn’t unique to work at a university, but is common across “white collar” professions in the United States. It also structures a global gig economy in which people are expected to become self-entrepreneurs who are committed to grinding in order to boost their own ratings. The shakeup of labor routines and enormous rise in unemployment during COVID-19 may have disrupted the expression of this kind of work flow for millions of people. But as we found, it remained active in the games we played and how we played them.

Part 2: Playing Together

You don’t have to play BOTW in a way that focuses on compulsive quest completion. Our friend Ashlyn Sparrow played for 60 hours without following the primary narrative or ever riding a horse. Our friend Heidi Coleman experienced the game mostly through ambient observation and breakfast conversation with her family who played during any free hour of the day. Other friends completed all the shrines but avoided boss battles. Still others played in an instrumental and linear fashion, without exploring the world’s secrets and emergent play opportunities. Moreover, on YouTube, we watched virtuosic players who fashioned their own metagames by speedrunning the game, completing it as quickly as possible with various self-imposed constraints (e.g., feeding all of the dogs in the game as quickly as possible).

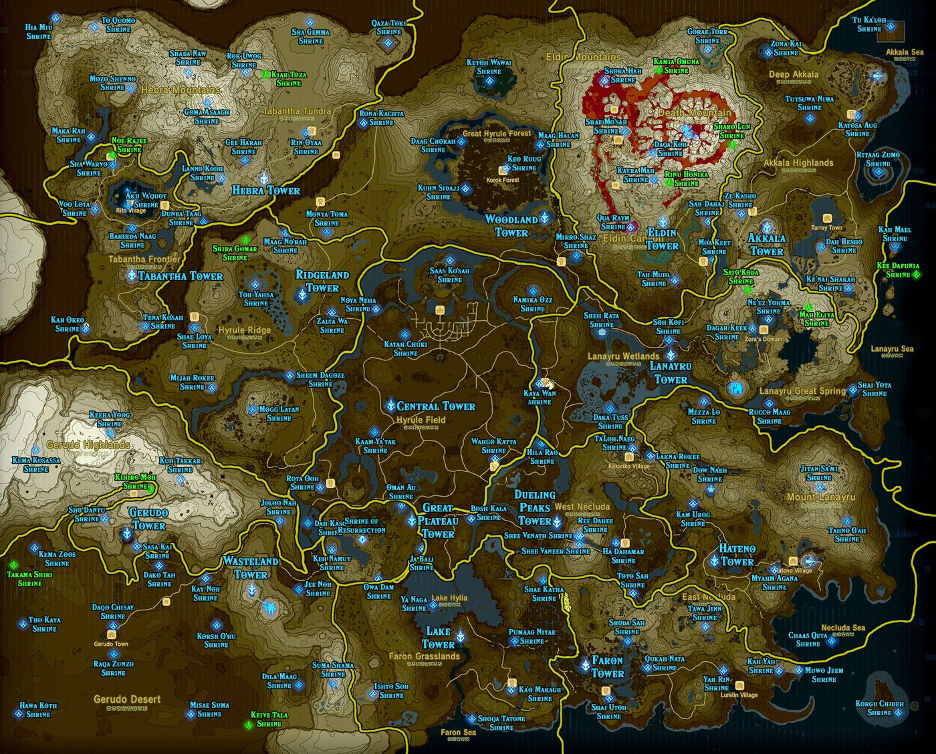

The vast world map of BOTW includes 120 shrine locations with unique puzzles.

In our case, the structure and quests of BOTW felt calming. In our everyday lives, we experienced constant rule changes. Access to spaces at the university was revoked, temporarily reinstated, and eliminated again. Movement to beloved locations in our own city or across national borders changed from week to week, creating consequences for us, our students, and our families. Amidst these frequent shifts and inconsistences, BOTW offered something more than mere escapism: it allowed us to gain focus through the consistency of rules, mechanics, and objectives. Perhaps most of all, the quest structure of the game produced a clear matrix of achievable tasks.

We approached BOTW not just as players but also game designers. During our months of shared play, we also worked with three colleagues to create an alternate reality game to spur creativity and build community online for students, staff, and faculty during the pandemic. This game, entitled A Labyrinth, combined a synchronous, cooperative, and multiplayer “Choose Your Own Adventure” game livestreamed via Twitch with 140 asynchronous quests that could be completed by teams across a six-week span. In many ways, the ethos of the game that we designed borrowed directly from both the freedom and constraint we found satisfying in BOTW.

Screenshot from the quest-based A Labyrinth alternate reality game that we designed with colleagues during COVID-19.

When we played BOTW, we didn’t do so as it was intended: that is, as a single-player game. Especially early on, we played many hours of the game together, trading the controller back and forth across couches, as we built up our stamina and health, so that we could pursue more challenging side quests, shrines, dungeons, and boss battles. But we also found pleasure in playing separately—spending time on our own watching the majestic dragon Farosh fly over Lake Hylia in order to learn its routines, swimming in the Goron hot springs while admiring the gorgeously detailed environments, and searching for and stealthily approaching the elusive Lord of the Mountain on the pool atop Satori Mountain.

We each developed specializations. Kristen led the way with armor upgrades, longer side quests, and cooking. Patrick took the lead with combat-based quests, dungeons, and boss battles. We both worked together on puzzles in many of the shrines. Beyond time spent in the game itself, when we had insomnia—a frequent visitor in the early COVID months—we would plan our next BOTW campaigns or brainstorm about how to solve tricky shrine puzzles.

We also engaged in shared analyses of the BOTW mechanics, narrative, characters and world design—for instance, the “exotic” women of Gerudo Town. To access this gender separatist town, Link (gendered male in presentation and in dialogue) must adopt a veil and traditional Gerudo attire for women in order to “pass” through the gates. Link also encounters a series of what can be read as queer characters, such as Vilia: the Hylian character who sells Link the gender specific clothing required to access Gerudo Town. Dressed in pink from head to toe, Vilia confounds the rumor around town that they are simply a voe in vai’s clothing. There is also Bolson, the head of the construction company in Hateno Village, who stylishly builds a house for Link in his pink pants, headdress, and earring. Both characters are coded in stereotypical ways, whether it is Bolson’s high, sing-song voice or Vilia’s falsetto. It is easy to eyeroll these representations as too flat, but we took them seriously as part of our emergent world making in BOTW—so seriously, in fact, that we started performing Bolson’s trademark dance IRL.

The relaxing and reviving Goron hot springs in BOTW.

Beyond our shared social connection, we also tapped into an amazing online community that had experimented with the game. We geeked out with friends and students who had or were playing it. We watched YouTube videos to learn new tricks. We read information-packed wikis to hone our skills. We skimmed Reddit threads to observe different play styles, and read fan arguments for why Bolson and Karson, his butch sidekick, are an item. Playing this game became an extension of our daily project of queer worldmaking realized in our nonnormativity, alternative life pathways, commitments to organizations such as the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality at our university, and serious game design projects focused on social change.

As we played The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, we asked ourselves: What does it mean to play a video game together in 2020? The experience gave us a shared work of art to access as a centerpiece of daily discussions, strategy sessions, metagaming experiments, and social connections. The experience of watching a film or television series, or reading a novel, with another person is arguably different. A film might spur a short spirited conversation after viewing, but rarely organizes multi-month or multi-year discussions among fans online and in person. Serial television series come closer, because one lives with a world and its characters over several years. But there responding to a linear television series is comparatively passive. And then one can discuss a novel, but people often read at varied paces and largely don’t experience a novel “together” except for in later analysis. An open world video game is, well, a world. Even 200+ hours into the game, we knew that all of its secrets were not exhausted. We’ll admit that, to this day, we still haven’t discovered all of the 900 Koroks hidden across the world!