Surviving Toxic Masculinity

by Christopher Breu, Contributing Editor

The Last of Us and The Last of Us 2 are best characterized as “survival realism.” The games combine the emphasis on biological horror associated with survival horror with the meticulous attention to everyday life associated not only with the violent realism of military-based shooters but also the more quotidian realism of games such as Life is Strange and Gone Home. TLOU2 queers genre conventions, transforming what AAA games can do. This queering of genre, in which its conventions are undone or rewritten, creates a space for the emergence of playable queer characters. With a few exceptions, AAA shooters and survival-horror games are not generally known for their progressive representations of gender and sexuality. Mainstream shooters like the Call of Duty or Battlefield franchises not only feature macho military exploits but also reinforce ideas of toxic masculinity

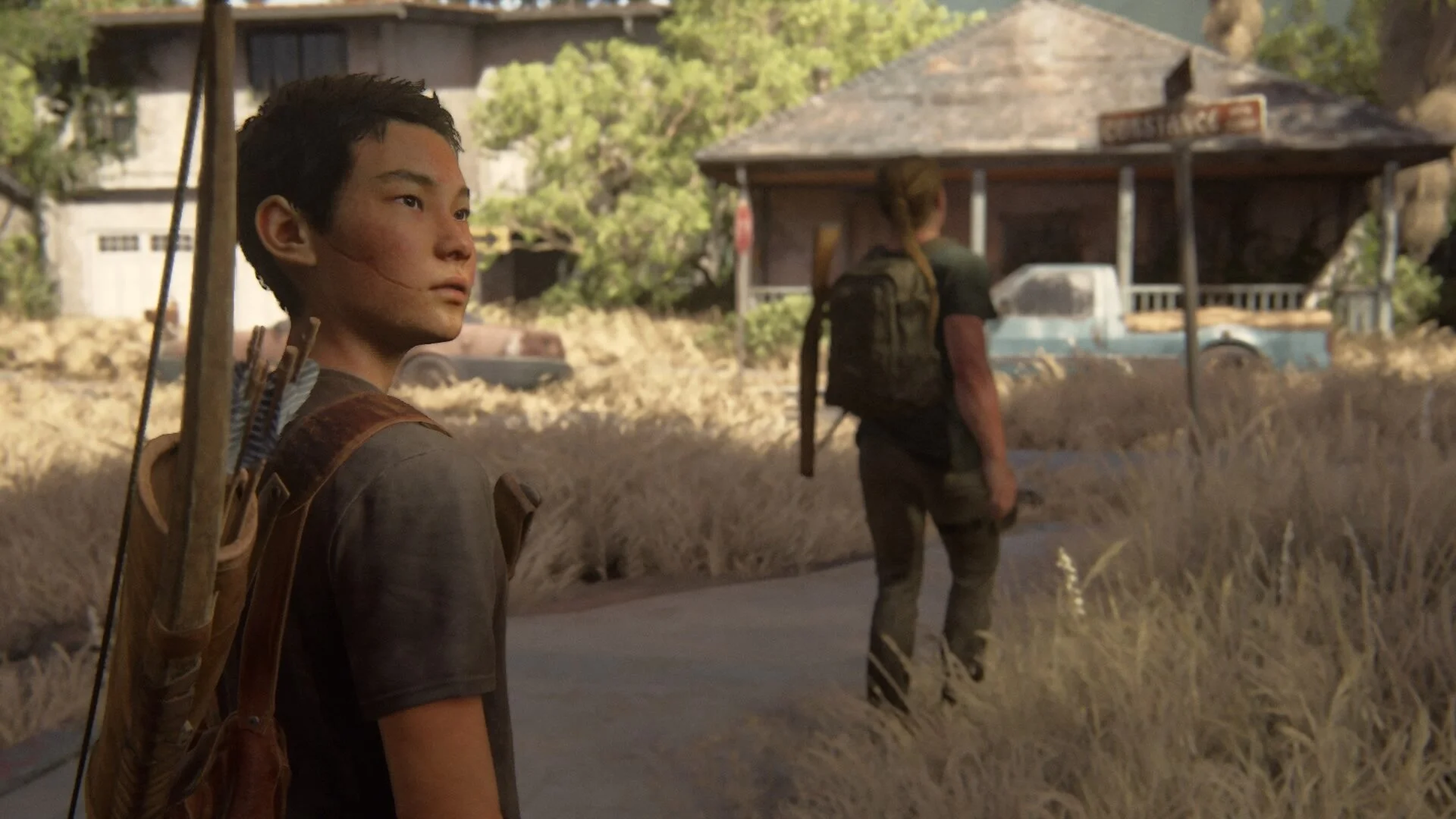

Gamers generally turn to endlessly customizable characters of RPGs or to indie games for progressive representations of gender. TLOU2 represents something unique in the gaming landscape: a AAA game organized around the tropes of shooters and survival horror, in which the player characters are predetermined but still don’t fit into the rigid constraints of heterosexuality, whiteness, or binary gender. The main character, Ellie, is lesbian, and she’s involved in a very believable way with Dina, a bisexual Jewish woman. Moreover, the game’s other major pairing (non-romantic, in this case) features a muscularly powerful female heterosexual character, Abby, who queers typical gender binaries and, Lev, an Asian trans man. While the representation of Lev has been the focus of some criticism, the representation of these pairs of nonnormative characters is certainly groundbreaking for a AAA game.

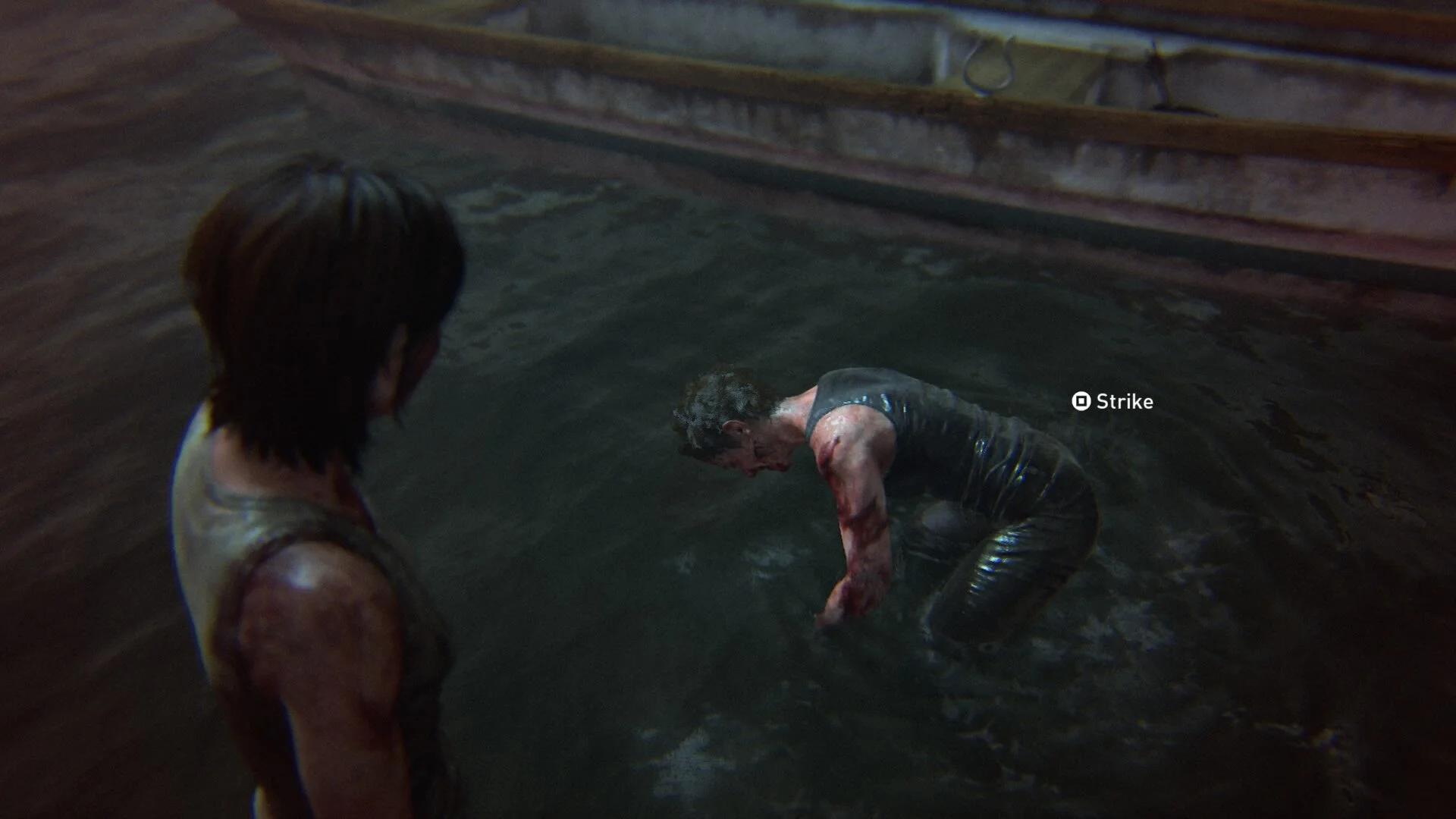

Yet, for all the game’s progressiveness on the level of individual characters, it’s in its larger vision that its limitations on the level of gender become evident. The game is great on gender understood on an individual level. Yet, its broader vision of gender is much more conservative. While the game represents a diversity of gendered identities, all of these are written under the banner of violent masculinity. Abby and Ellie are the most badass characters in the game precisely because they prove themselves to be tougher and more brutal than any of the other characters. Ellie, in particular, resorts to torture and treating Dina’s pregnancy as a hazard. It’s striking that the only other pregnant woman depicted in the game is shot by Ellie. Pregnancy clearly makes you a potential victim in the game. It’s tied to both futurity and to conventional femininity and the game has very little room for either.

These larger-scale forms of gender ideology are tied to genre. It’s the game’s inability to complicate its largest genre borrowings that finally limit its vision. In addition to military-style shooters, the game is just as indebted to that most ideological of American genres: the Western. The group of survivors that Ellie begins the game with seem to be made up entirely of macho cowboys and genderqueer women. What’s missing is any kind of genderqueerness or trans identity that’s represented as both feminine and tough; being feminine, in the game, is stereotypically presented as a mark of weakness and domesticity. Instead, we get an almost classic version of the Western narrative, right down to the figuration of the Seraphites as an Indian nation dwelling on (as far as we can make out their location) present-day Suquamish lands and a penultimate scene in which Ellie leaves Dina and their domestic farm life to finally get revenge on Abby, who tortures and kills Joel earlier in the game.

The end of the game complicates this masculine view of things somewhat by charting the costs of Ellie’s adherence to toxic masculinity (Dina leaves her) and constructing a final truce—overseen by a ghostly vision of Joel—between Ellie and Abby. But the game finally represents the limit of ideas of individual inclusion around gender and sexuality that do not challenge the fundamental gendering of American culture. Like allowing gays in the military, it may be progressive, but progressive in the name of affirming a violent and often toxic masculine culture. The game thus feels like a mirror on the contemporary United States in our moment. We fight for individual freedoms, yet we often miss the larger forms of collective ideology against which we also need to struggle.