“Fuck All These Groups”

by Brian Rejack, Contributing Editor

Towards the end of The Last of Us Part II, after experiencing hours of devastating brutality and horror, it’s hard not to start feeling a bit hollow. Despite Ellie’s recommitment to her quest for vengeance in the game’s final act, I think by then she’s wondering about the point of it all, too. Never does she sound more deflated than when convincing herself to keep going as she moves through Santa Barbara looking for Joel’s killer. So I get that she’s feeling deeply apathetic and cynical when she writes in one of her final journal entries: “Scars. Wolves. Fireflies. Fuck all these groups.”

The thing is, though, that sentiment isn’t just an idle comment from Ellie—“fuck all these groups” is the only ethic that remains by the end of this revenge tragedy. Particularly because I was playing this game during June 2020, when so many forms of collective action were happening across the US, and across the world, in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, I kept returning to this recognition: The Last of Us Part II cannot effectively imagine any lasting notion of collectivity. Time and again the game suggests that the only viable option in response to a collapsing social order is some version of Ellie’s dismissal: “Fuck all these groups.”

By collectivity I don’t mean just any sort of group belonging. Rather, the game refuses to accept the possibility of a collective as an intentional coming-together of people aiming to address and redress the world in order to remake it in a better form. The groups presented in The Last of Us Part II are only ever one of two options. They are fundamentally insular, interested only in preserving themselves, or they are failed collectives, corrupted in some irredeemable way from their original aims.

At the same time, the game also asks us to resist the impulse to say, “fuck all these people.” It suggests that all groups are fucked in the end anyway, so the individual is all that matters. This way of thinking leads to what has been the most discussed and debated element of The Last of Us Part II: the narrative decision to shift perspective at the midpoint and play from the position of the enemy. In order for that tactic to work, though, Abby’s failed collective, the Washington Liberation Front (WLF or “Wolves”), is portrayed as just good enough that we can still empathize with the individuals who belong, or once belonged, to it. The same goes for the Seraphites (the “Scars” of Ellie’s journal entry). That group, too, is good enough that Abby can rethink her perspective on Lev and Yara, and even learn from the less-horrible parts of their religion. Nevertheless, all groups must ultimately be cast as failures so that the player can feel justified when killing so many of their members. The people we kill are just members of flawed groups; the people we play are heroic individuals who escape the corruption of failed collectives. No good groups, only good people.

The narrative and emotional results of playing as Abby, the arch-villain in Ellie’s eyes, are indeed impressive, and that risk adds complexity to what would have otherwise been a pretty straightforward story (sorry, Ellie, I’m on Team Abby now!). But because of the narrative’s wholesale rejection of collectivity, the perspectival shifts ultimately land in troubling ethical and political territory. The impulse to decry groups and empathize with individuals has a logical end point that the game seems oblivious to, and that I’m really not cool with: there were very fine people on both sides.

The problem, of course, is that some sides are too bad to have good people on them. As far as I can tell, The Last of Us Part II isn’t capable of reckoning with that fact. It wants to discard all collectives and embrace individuals, but it does so without acknowledging that individuals are made by their groups just as groups are made by their individuals. When encountering the game’s final foes, the Rattlers, whose M.O. is to go around enslaving people, I found myself wondering, “is Naughty Dog going to release DLC in which we play as a Rattler and empathize with how they dealt with their complicated feelings about enslaving people?”

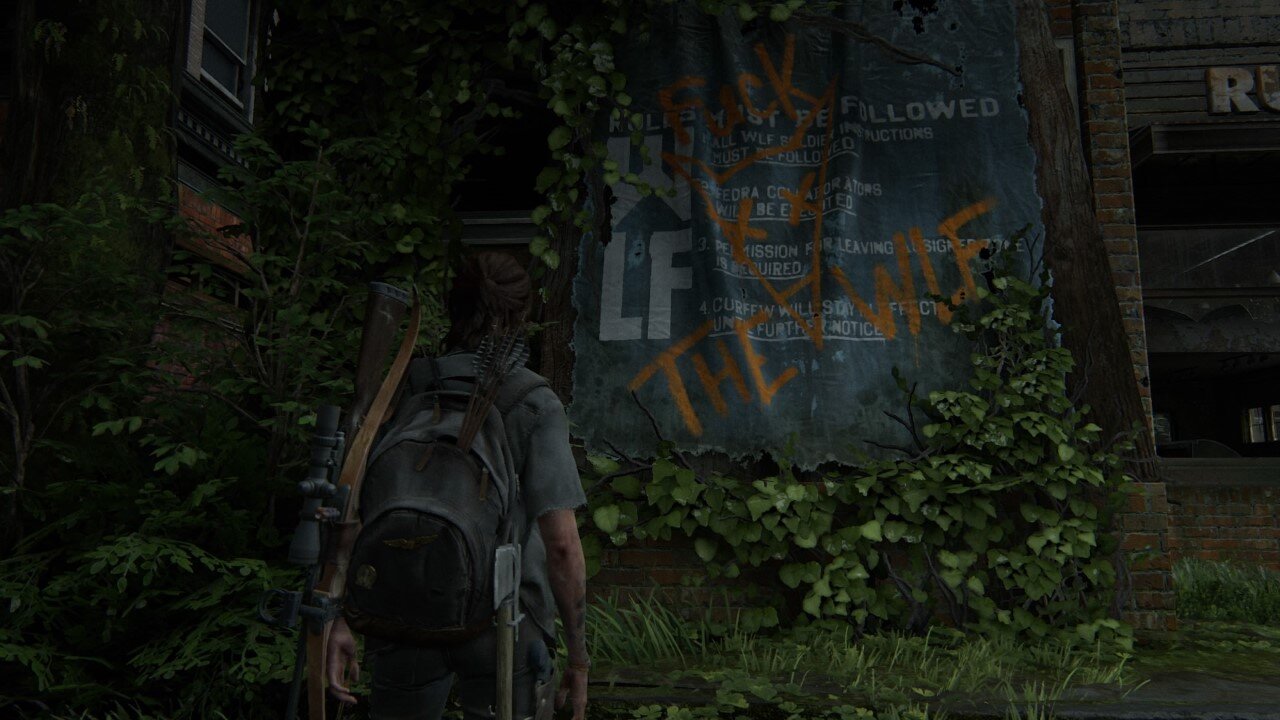

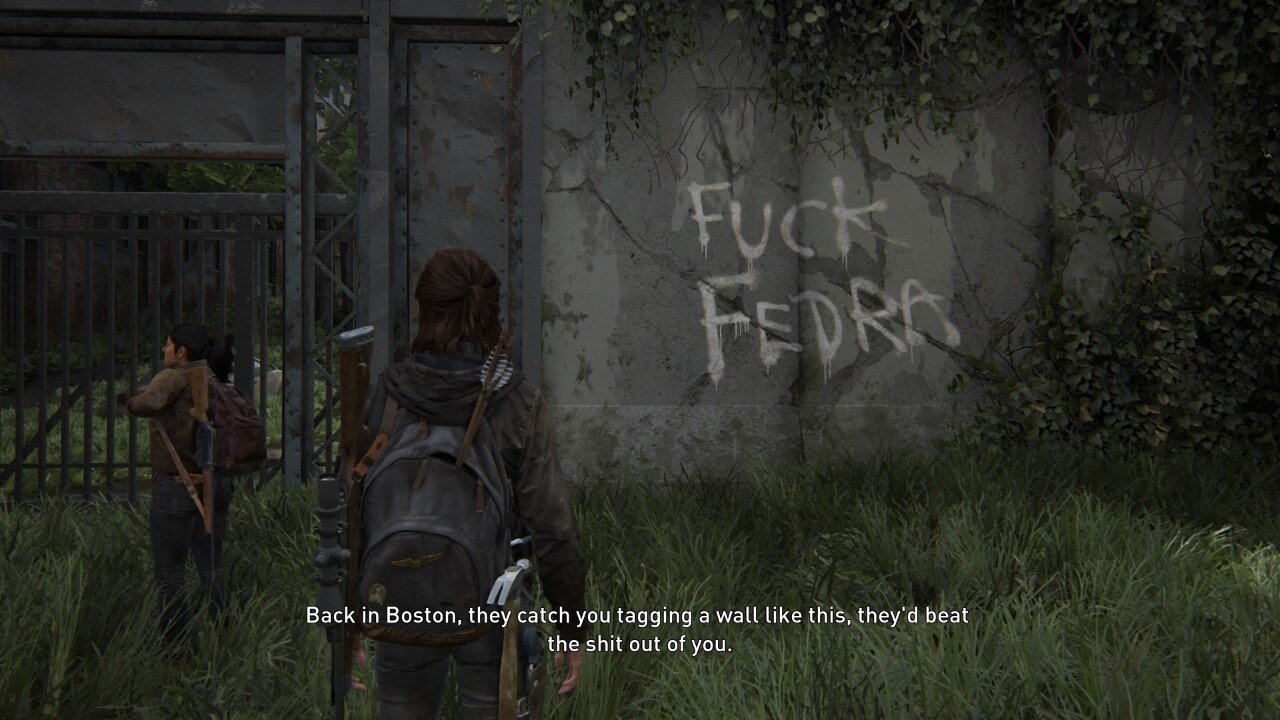

I admire and love a lot of what this game does. It is beautiful and moving and wonderfully crafted. But it also feels full of missed opportunities. The game’s world could have featured vibrant, if still flawed, collectives. Instead, it lazily equates all groups as similarly doomed, making individual acts the only possibility for goodness. Upon arriving in Seattle, Ellie and Dina spot some graffiti reading “Fuck FEDRA” (the acronym for the totalitarian occupying force). Soon after, Ellie comes across graffiti that reads “Fuck the WLF.” Sorry, but 2020 is the time to build and join collectives, not to dismiss them. So I hope that Abby and Lev manage to reach the Fireflies, and that someday Ellie goes to join them.