Cozy Grove & Cottagegoth

Nate Schmidt, Contributing Editor

There has to be something a little bit melancholy hiding at the core of Animal Crossing, because everybody else wants to make games that put anthropomorphic animals in depressing situations. Night in the Woods: it’s Animal Crossing characters with angst. Spiritfarer: it’s Animal Crossing characters with death and boats. Most recently, there’s Cozy Grove: Animal Crossing with ghosts.*

Night in the Woods: The people are animals. The angst is all too human. I took this screenshot.

(*I know that Animal Crossing already has a ghost named Wisp. Since you can’t die in Animal Crossing, it’s frankly a little bit weird that Wisp is in there. Like, is that the only person who ever died in this universe, or the collective consciousness of all who have died in this universe? Is becoming one with Wisp the only afterlife for those who somehow exceed the boundaries of Animal Crossing’s deathless sphere?)

Even though these games are as different from each other as blueberry pie and ice cream cake, they each offer an answer to an important question: “What if Animal Crossing took a break from its constant sunshine and sparkles cottagecore positivity and engaged with something bittersweet, melancholy, or morbid?” I would like to offer a name for the many different answers to this question: cottagegoth.

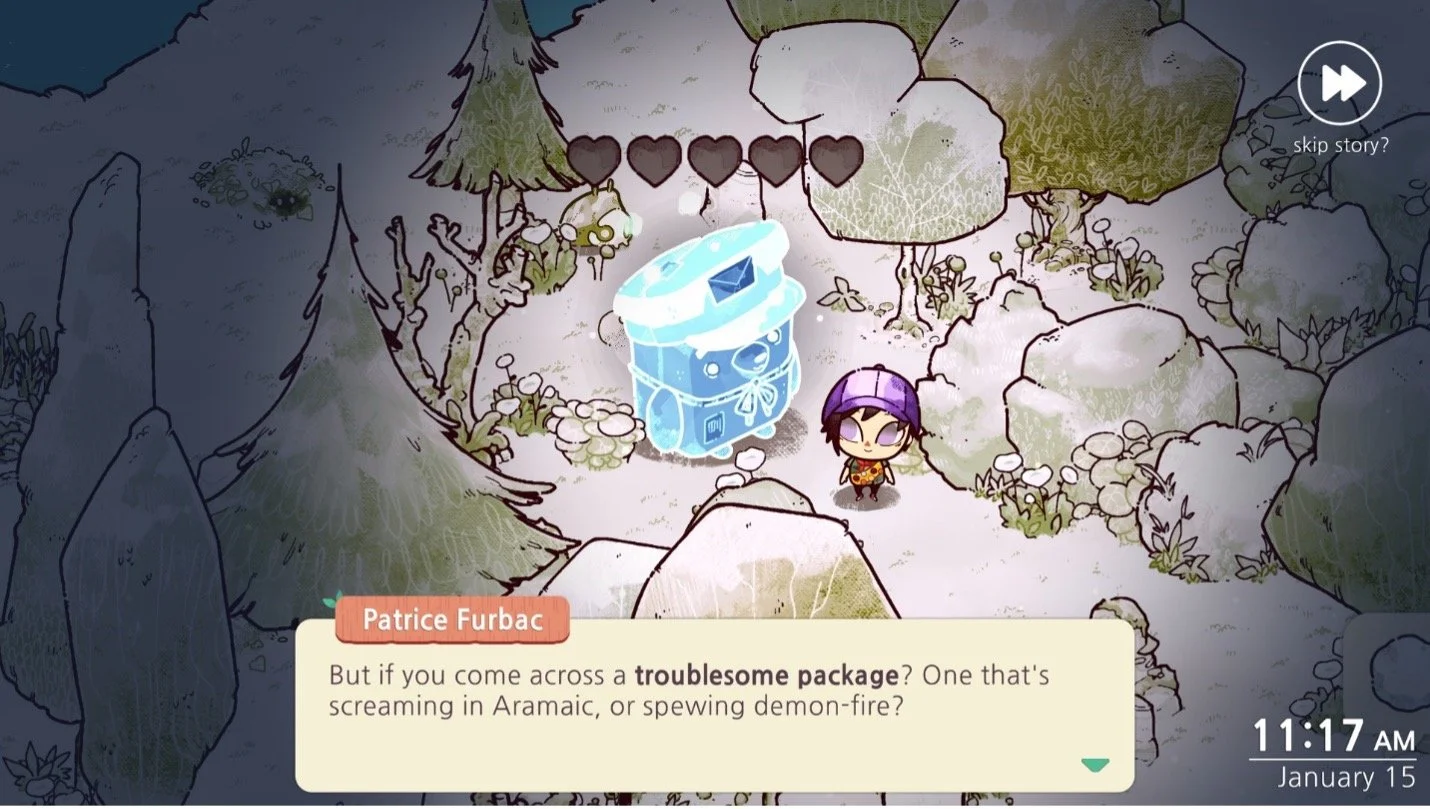

Cozy Grove.

I think of cottagegoth as an aesthetic choice that acknowledges the pleasures of fanciful escapism while remaining mindful of the final void towards which we’re all headed. It is a cross-stitch memento mori, a DIY planter set off with melty candles and velvety drapes. It’s also a term that I’m not the first person to use. The r/cottagegoth subreddit was started in June of 2020 and has four and a half thousand people. Out of all those people, it would be bananas for me to think that I am the first one to apply it to video games, either. However, I would still like to borrow the term for a moment in order to think more closely about what it means to play Cozy Grove—or Animal Crossing with ghosts.

I don’t think I am being unfair to Spry Fox, Cozy Grove’s developers, when I describe the game in this cheekily simplified way. The game wears its influences on its sleeve; there are a number of obvious callbacks to Animal Crossing: New Horizons. See if any of this sounds familiar: You appear on an island. Once on that island, you walk around and help a bunch of anthropomorphic animals accomplish various tasks while catching fish, collecting furniture, and learning DIY recipes. By accomplishing these tasks, you also make money, which you can use to upgrade your stuff and get access to new items. All of these things happen in New Horizons and in Cozy Grove.

Cozy Grove.

Now, Cozy Grove has some important differences from New Horizons that make for a more compelling game in some ways. In Cozy Grove, you are a forest scout who has been dispatched to help ghost animals recall things about their past lives, not just some rando out to make your own house the biggest one on the island. You can acquire animal companions and take an active hand in their care, and your relationship to the ghost beasts on the island is one of mutual education and assistance, unlike the New Horizons villagers who could all disappear tomorrow and not change a thing about how I play the game. (Maybe I’m playing it wrong?) The game’s early reliance on hidden object quests is going to be frustrating for people who just want to craft cute furniture, and some other jobs you might do for the ghosts can be annoyingly time-gated, but my overall sense is that Cozy Grove goes out of its way to insert mechanics from the Animal Crossing series into a meaningful narrative.

But we need to talk about aesthetics, because that’s the major difference between Cozy Grove and Animal Crossing: one has demon-possessed letters and lets you craft things with charred fishbones, while the other only deviates from its relentless cheerfulness once a year at Halloween through a convoluted system of candy exchange. Animal Crossing, as both Vox and The New York Times will tell you, is cottagecore. Cozy Grove is cottagegoth, and I’d like to invite you to think with me for a moment about how that distinction is relevant in relation to the brand of pastoral escapism offered by both games. I have three theories about this.

Cozy Grove.

Theory number one: the cottagecore escape of Animal Crossing is too happy, so it feels edgy and satisfying to subvert it. This is perhaps my least charitable theory, but I think it’s a legitimate enough feeling not to be dismissed out of hand. The Animal Crossing games are relentlessly chipper, and New Horizons has arguably gone the farthest in toning down or erasing all of the weirder, harsher elements from earlier games in the series. Remember when Tom Nook was kind of a skeevy landlord who bossed you around and told you what clothes you could wear? Remember Resetti, who used to yell at you and pretend to delete your game, but is now responsible for rescuing you if you get stuck? I think we turn to New Horizons because it can be a honeyed antidote to everyday life and its troubles, but I find that too steady a diet of its happy-go-lucky charms eventually feels saccharine and stifling. Adding some skulls and spirits to the mix makes the escapism more palatable, like a pastry washed down with bitter black coffee. Cottagegoth games like Cozy Grove and Spiritfarer offer customizable imaginary spaces without forcing the player to always be so damn peppy about it.

Theory number two is a more nuanced riff on theory number one: cottagecore-style escapism is not as fulfilling when it ignores one of the most important things about human existence, while cottagegoth games are willing and eager to take death into account. (A caveat: I am talking specifically about video games, not about real-world design communities on Instagram.) As shows like The Good Place remind us, death makes living meaningful. A life sim that ignores death offers only the emptiest kind of wish fulfillment, because we all know that anything profound about our lives off-screen comes from the fact that we will, someday, never do or think or say anything ever again. The playful morbidity of cottagegoth games is therefore not just a stylistic choice, but an homage to the things that make life more consequential.

Ephemeral joy! Don't worry; it will be a useful resource later on. I took this screenshot too. I took all these screenshots.

Last theory: there is something about escapism that makes us think about how we will eventually shuffle off this mortal coil, and that’s what makes it satisfying to subvert a cottagecore game like New Horizons into a cottagegoth game like Cozy Grove. I know this sounds terribly morbid, and it’s actually going to get worse here for a second before it gets better, but bear with me (pun intended, for those who have played Cozy Grove).

Sigmund Freud used to talk about the “death drive.” At first, he thought that people primarily pursue pleasure, but the more he actually observed human beings in action the more he saw that people have all kinds of melancholy behaviors that have nothing to do with pleasure at all. Freud thought there must be some other drive besides the one for pleasure that can adequately account for all the depressing stuff that people do, and he eventually settled on calling it the death drive.

But here’s the thing: the death drive makes us want to do all kinds of painful things, but it’s ultimately a desire for peace, for quietude. When I run a difficult conversation over and over again in my head, for example, it's not because I want to relive that moment. It’s because I’m still struggling to be at peace with it. It is pleasurable to escape from real world problems into a peaceful digital space, but there is always has a little bit of that melancholy death drive at play. On some level—I might even go so far as to say an “unconscious” level—developers and players look at Animal Crossing’s representation of an endlessly peaceful alternate reality and recognize that anytime we’re talking about being completely carefree, we’re talking at least a little bit about that long silence in which we will all one day come to rest. That’s why we decided that our escape fantasies need ghosts.