Self-Love and Companionship in We Know the Devil

Nathan Schmidt, Contributing Editor

Note: The following contains major spoilers for the visual novel We Know the Devil, so think about playing it first! You can get it here for $6.66. Also, if you read this piece and say his name three times, Lucifer himself pops out of your laptop screen and wisks you away to the most devastating moment of your younger self’s summer camp days.

You’ve either had one or you haven’t: there is no romance like church camp romance. The surreptition, the wistful longing across the campfire, the bittersweet cocktail of guilt and euphoria stemming from the most incidental touch—and the more you lean into the whole “my eternal destiny is riding on whether or not he and I make out” aspect of it, the more exponentially consequential it all feels. These kinds of adolescent experiences always have their rules and taboos, their frustrated camp counselors, and every kind of brilliant juvenile circumnavigation of authority, but church camp…church camp is its own place, that can make a heaven of Hell, a hell of Heaven. I don’t know how—or if—anybody comes home okay from church camp.

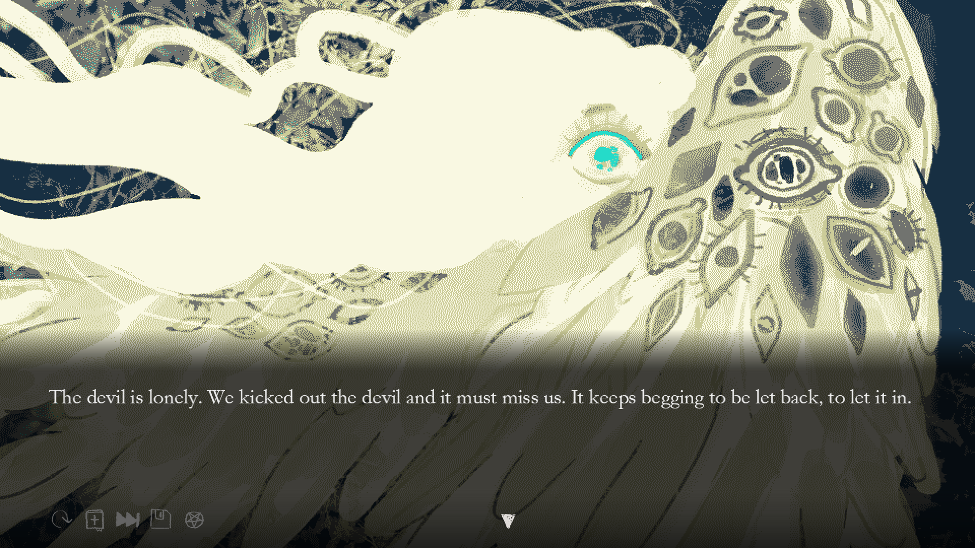

We Know the Devil is a visual novel in which three queer kids who are trying to figure out if there is a way to come home okay from church camp. Each of them is invested in camp to various degrees. Neptune is totally checked out of things and is always on her phone. Jupiter is so used to performing excellently that she can more or less keep her head down and power through. Anxious Venus would really just like to get the whole thing over with. As the story’s Lynchian 35mm photo backdrops and threatening score will tell you, there is something very wrong with this particular camp. “God” and “The Devil” aren’t just abstract entities here—there is a whole system of sirens and radios rigged up to let one in and keep the other out…mostly.

As the narrative progresses, it branches off from the various points at which you have to make decisions about who is left out of the action. Maybe you need to climb up a pole to fix the sirens that warn the campers when the devil is coming, but there’s only room for two up there. Maybe you all get drunk on bootleg alcohol and play truth or dare, which means that there’s just one person asking the questions and one person answering. Maybe two of the characters just want to gossip about everybody else at the camp behind their back. Whatever the rationale or the circumstances, the only way to advance the story is to leave somebody out. And, by the end of the story, whoever gets left out the most is going to become the devil.

The first time I played this game, that’s what I thought it was about: companionship, and the subtle decisions people make together about inclusion and exclusion that can have cascading consequences. It’s not a story bereft of romance—this is still summer camp we’re talking about—but my overall first impression had more to do with the various interpersonal relationships in the story, and how the choices to involve certain characters over others led them to encounter things they had been repressing, which they embodied when the devil took over.

But We Know the Devil has a more memorable, more compelling story to tell. You see, in each of the possible endings where one of the characters becomes the devil, the whole cast has a little conversation with God right before the sirens start to go off. God is on the radio (you can find him at 109.8 fm) and never stops to check in with you—he always assumes you’re already listening. To quote the game narrative, he sounds “like every boy you are afraid of talking at once.” Depending on who is going to be the devil this time, he always has some proverb or proclamation that touches on that character’s deepest fears and desires, which in turn influences how the devil gets embodied. One character spends most of the game trying to repress her feelings for another girl and trying to square them with her internalized belief that it is a sin to touch and be touched by other people. When she becomes the devil, the room fills with a mass of disembodied hands—“a hand for every kind of touch,” as the game says. In this, as in other endings, the moment the character becomes the devil, she gets this quick monstrous moment of freedom, letting the things she has been repressing take over before the other two do their duty and kill her. Every time, it’s ambivalent and scary and so, so sad.

It is possible, however to complete the game in such a way that you get a fourth ending. And in that ending, the gang tries to tune in to God and gets the dulcet tones of the devil over the radio instead. At this point, questions about inclusion and exclusion get subsumed as the devil makes an offer: “There is room for three in my world, and only two in his.” When all three become the devil together, well…a lot of things happen. It’s no fun if I spoil everything for you. But this ending gives you a chance to imagine a world where Venus gets to leave her male body behind for good, where Jupiter has a hand for every kind of touch, where Neptune is no longer haunted by the tyrrany of being “good”—where nobody has to kill the devil because there’s nobody around to do it.

So, okay, yes. It is a story about togetherness, camaraderie (or the lack thereof), friendship, romance, and desire. When we’re all the devil, we don’t have to worry about killing him. Depending on how you play the game, it can be a story about finding your community when it was right under your nose the whole time. But the thing about the game that I find most compelling is both more insular and capacious. In what one might call the “good ending,” each character gets to accept whatever “devil” she thinks is inside of herself. Being the devil is, in other words, a state common to all of us. And, when you find a community which refuses to see the systems of moral and religious authority that would vilify you as devilish, you get to know the devil from a position that is no longer fearful, but self-actualizing. You know the devil as well as you know yourself.

If, as a teenager, I had come home from church camp possessed by the devil himself…well, that would have been an awkward dinner table conversation. At the very least, though, I sure wish somebody would have come along who could have told me that my body, along with all the things it wants and needs, is good. Nobody did; it would take Walt Whitman and a community college English department to get that journey going. So sure, it’s February, the season of “the holiday invented by greeting card companies to make single people feel like crap,” as Jim Carey’s character says in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. But no matter what your position is vis-à-vis romance, its baggage, and our culture’s questionable expectations about it, there’s never a bad excuse to take a moment and love yourself—devil and all.

For more writing on video games and love (in all its many forms), check out to the introduction to our series “Love Connections” and Edmond Chang’s “Cruising Animal Crossing.”