The Poetry of the Atari 2600

Alexander B. Joy, Guest Contributor

It often confounds fellow Atari 2600 fans to learn that I wasn’t around for the console’s lifetime. (In fact, even a good chunk of the NES’s lifespan passed before I was born.) Since the 2600 played no part in my youth, my interest in it sometimes resembles nostalgia for a past that doesn’t belong to me – like collecting memories from a life I never lived. How else could one love the jagged, choppy gameplay of these old relics? Without the gauze of nostalgia, Atari 2600 titles show their age; without some correspondence to treasured childhood experiences, their value seems limited to historical curiosity.

Yet the humble 2600 cartridge gains new meaning in the age of the triple-A game. Major releases now drop with blockbuster fanfare, boasting multi-million dollar budgets and sequel-friendly scripts tailored to perpetuate franchise IPs. It’s no coincidence that Uncharted, given its aggressive emphasis on character and story, spawned a film alongside its many sequels, prequels, and spin-offs. One might conclude that modern gaming, favoring plot and persona as its driving engines, now tends less toward the novel than the novelistic: they’re story engines first and foremost, where the player’s primary reason to play the game is to learn what happens next. Against this backdrop, the 2600’s design philosophy presents an alternative – if not an antidote – to narrative-first experiences. For if today’s headliner titles resemble novels, then Atari 2600 games read more like poems.

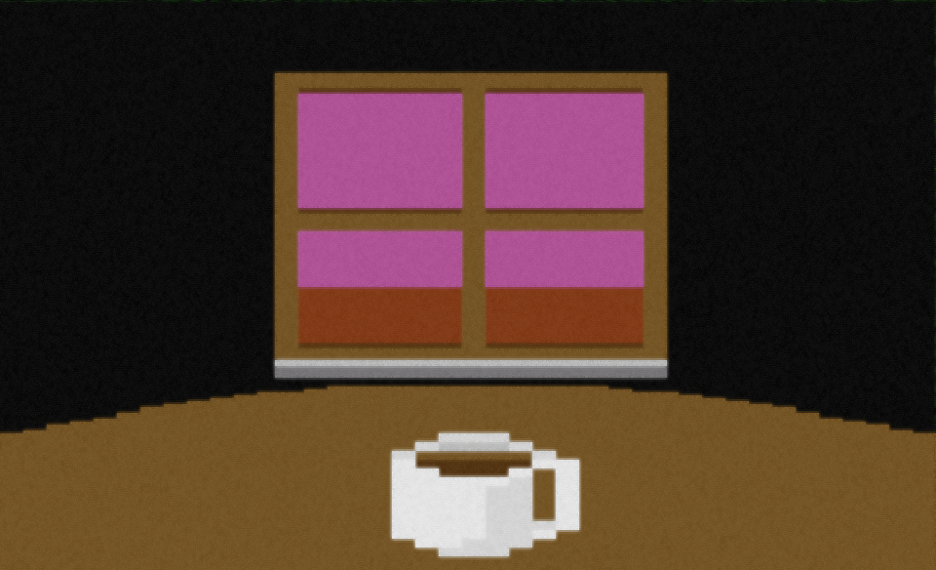

The 2600’s limited capacities – and stringent coding requirements – mean that its games must do more with less. This minimalism foregrounds the sorts of things that poems normally do. It privileges an immediacy of experience that functions as the beginning of a thought, inviting the player to follow its thread. Consider Ian Bogost’s 2010 homebrew cart, A Slow Year, which Bogost dubs “a chapbook of game poems.” It comprises four haiku-like scenes corresponding to the four seasons: observing rain over neighborhood roofs, watching sticks drift across a lake, attempting to catch falling leaves, and drinking coffee during sunrise. “As poetry,” Bogost writes, “they rely on the condensation of symbols and concepts rather than the clarification of specific experiences. As images, they offer visually evocative yet obscure depictions of real scenes and objects.” It’s the simplicity of the Atari 2600’s graphics – and the accompanying need to distill each scene down to its essential components – that elevates A Slow Year’s otherwise commonplace situations from mundane to transcendent.

There’s little reason to believe Bogost’s insights should apply to A Slow Year alone. His artist’s statement furnishes an instruction manual for reading Atari 2600 games in general, and a primer on how they gain their evocative powers. The objects and events onscreen gain emotional or allegorical weight by virtue of providing no extraneous information. Like watched clouds assuming shape, they have contour enough for players to discern recognizable forms, yet remain sufficiently featureless for players to map their own interpretations within them. We don’t need a backstory explaining how the crew of the S.S. Triangle ended up stranded in an asteroid field in order to grasp the urgency and desperation of their predicament; it’s enough that Asteroids places us in the thick of things, letting us perceive and articulate its significance for ourselves. No narrative or character makes explicit what we’re supposed to think or feel, and the experience is richer for it. Like any line of good poetry, an Atari 2600 game affords glimpses of wider worlds and deeper thoughts that we may explore as we please.

Although this poetic approach remains uncommon among major studio releases, we can give thanks that it didn’t die with the Atari 2600. The ethos persists in today’s indie development scene, where brief, powerful experiences or inspiring software samples occupy significant space. Plenty of games on noted indie distribution platform itch.io, such as cecile richard’s novena, call themselves “poems.” Enthusiasts of the “fantasy console” PICO-8 salute toys and tech demos (including Jakub Wasilewski’s Blue Marble); creator Joseph White, or “Zep,” regularly retweets such artifacts under the handle @lexaloffle. Homebrew developers even continue to shower the Atari 2600 with love, amassing substantial enough audiences to support a storefront selling actual cartridges.

My own fondness for Atari 2600 games is rooted in appreciation for their poetic qualities. In trusting players to think and feel for themselves, they offer a level of respect that’s largely absent from modern studio products. When I boot up an Atari 2600 cartridge or ROM, I know I’m in for a restrained, elemental experience whose importance I’ll have to determine for myself. But I’d have it no other way, because reaching that determination will be a journey that no one else could have plotted for me.