Can Curation Save Us from the Indiepocalypse?

Nathan Schmidt, Contributing Editor

Look, I’m not going to argue that something like the “indiepocalypse” predicted in the last decade didn’t happen. I can’t speak to this from my own experience, but it doesn’t seem like it got easier to be an indie developer— at least, if your goal is to be financially successful. No matter how many years you spend on a passion project, it can still get buried on itch.io or Steam (although one of these platforms does a much better job than the other of highlighting a broad array of interesting work from emergent creators … and it’s not Steam). And the success of indie games that do manage to grab the attention of a huge audience can seem like it comes without rhyme or reason, ruled by nothing but the anti-law of chaos that sets the terms for internet virality.

The thing that still bugs me about this indiepocalypse idea—even though it originated in the internet equivalent of the Pleistocene era—is that the so-called “saturation of the market” was somehow the fault of the developers themselves. This is the same abusive logic that capitalism always uses, right? Capitalism always says, “I’m not the problem! You’re the problem!” In this case, as in most others, I have a really hard time accepting that as true. Democratizing the means of production (by which I really mean, “a bunch of people having the ability to make their own games,” but speaking in obtuse jargon is my only superpower) isn’t a problem. Like Anna Anthropy said back in the Mesozoic times (2012): “What I want from videogames is for creation to be open to everyone, not just publishers and programmers. I want games to be personal and meaningful, not just pulp for an established audience. I want game creation to be decentralized. I want games as zines.” And then, as soon as games as zines basically happened for a lot of people, everybody started complaining about “market saturation” as if this were somehow the game makers’ fault.

That’s why it’s so meaningful that Andrew, alias PIZZA PRANKS, decided to call his curated monthly bundle-zine Indiepocalypse. The project is a response to the event from which it derives its name, but it never treats the fact that a whole bunch of people can make video games now as a problem. In the preface to each issue of the zine, Andrew acknowledges that it can be really hard to be an indie game developer and that it hurts to see years of work go unnoticed, but he never blames the problem on the creators themselves: “The entire culture [of gaming] leads to impossible expectations of what a small team (or single person) can create and the overall devaluation of ‘smaller’ games,” Andrew writes. “It is my goal with this anthology to change that culture to better appreciate these games and the developers who make them.” By situating the locus of the problem at the level of gaming culture, Andrew sets himself a high bar, but he also leaps over a number of pitfalls that others haven’t been so adept at avoiding.

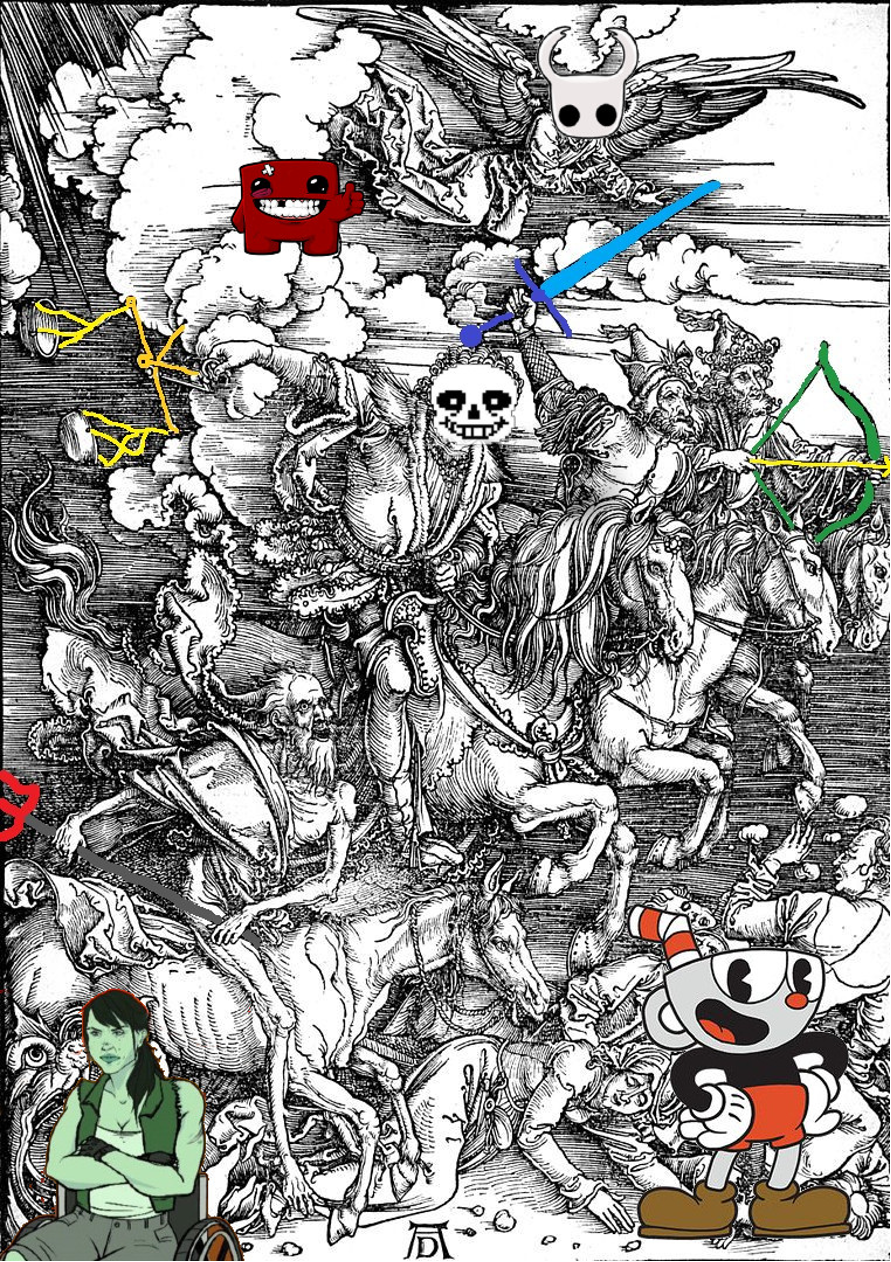

The powerful assumption here is that some gentle curation will not just help people decide what to play, but can actually serve as a catalyst to change people’s expectations about indie titles so that we don’t expect every indie game to look like it was made by a team of twenty. Each edition of Indiepocalypse (available here) celebrates the fact that there are so many phenomenal creative voices out there by handpicking a few and bundling them together in a zip file. They also come with a .pdf zine—an actual, DIY publication like the ones with the anarchist essays you used to find laying around the community college. The funny thing is that many of the games featured in Indiepocalypse fit precisely into the desired world described by Anna Anthropy nearly a decade ago: games as zines. As in, games for the people, by the people. Games bound together with the electric equivalent of staples. Games with something profoundly personal to say. In that sense, Indiepocalypse is the zine of the zines, the uberzine, if you will, that puts DIY aesthetics alongside renegade game development in a way that makes you feel like you’re part of a subculture again.

The curatorial mindset, while it doesn’t exempt itself from the social dynamics of power, can be a meaningful signpost to guide gaming culture away from the norm that only indies born of hype, crunch, or huge reserves of pre-existing capital are worth playing. As with any archive, the politics of curation are as important as the content of the zine, and Indiepocalypse really shines in its focus on games that center the experience of marginalized and underrepresented communities. Issue #11, for example, featured Laurie o’Connel’s Lichcraft, an “RPG for Trans Necromancers” about “being on an NHS waiting list [for trans healthcare] so long that you become in immortal necromancer.” The zine also highlights projects that push the limits of what counts as a game—an endeavor that, no matter how many times I think I’ve seen it all, never fails to surprise me (consider, for example, Cecile Richard’s Novena, a pixellated poem based on an ancient Christian devotional practice of nine consecutive days of prayer, featured in Indiepocalypse #6). Plucked like gems from what Carolyn Steedman calls “the great strandless river of everything,” the games in Indiepocalypse suggest a future in which voices that have been pushed to the margins are finally centered and where creativity eclipses slick production.

So, does it work? Can Indiepocalypse, the zine, fix the “indiepocalypse,” the phenomenon that is definitely more complicated than the fact that a lot of games exist? Probably not— at least, not by itself. But culture changes when a bunch of us together form a community and do things differently, and if we all pitch in and find equally compelling ways to share new and exciting discoveries, who knows what could happen? You might even start with this amazing electric zine maker (which was, incidentally, featured as an extra in Indiepocalypse #6). In spite of its eschatological moniker, Indiepocalypse is not an end, but a beginning. Curation is a first, significant step on the path towards community. When games become avenues for the best kind of (dare I say it) anarchical, anti-hegemonic means of self-expression, I think we can agree together that “too many games” is never going to be the problem. Instead, I think we’ve gotta bring back the zines. Zine culture has always been about microcuration, after all; a zine is basically a more fun, more radical way of saying, “Look what I found!” If we can all take some cues from the PIZZA PRANKS and take the time to be better curators for each other, I bet we would watch the “indiepocalypse” fade into the rearview mirror—with Indiepocalypse leading the way, of course.

Looking for some new indie games to play? Check out Don Everhart’s selection of games from Indiepocalypse!