This Machine Kills Fascists: Extreme Meatpunks Forever

Nathan Schmidt, Contributing Editor

“SUBTLETY IS FOR FUCKERS: if you’re going to say something then say it loud and say it clear. there are times for clever metaphors and there are times when you gotta punch a fash’s lights out and we live in the second time.” – Heather Flowers, Meatpunk Manifesto

There is a long and storied tradition of decimating fascists in video games. Hell, we’ve been mowing down Nazis since Wolfenstein 3-D, not to mention both of those Call of Duty games. Then we’ve got the Caesar’s Legion in New Vegas and The Patriarch and his goons in this year’s Wasteland 3.

And then there was 2017, and the online whining about Bethesda siding with “The SJWs” by having you kill Nazis in America, Man in the High Castle-style, in Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus. On June 12th, 2017, Vice and The Verge both reported on the newly controversial status of the phrase “Make America Nazi-Free Again.” This was exactly one month to the day before self-proclaimed neo-Nazi James Alex Fields Jr. slaughtered Heather Heyer by deliberately ramming his car into an antifascist demonstration at the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, VA. And then there was the president’s predictable response, which demonstrated for the umpteenth time that he is both a limp fascist-strongman wannabe and a massive dullard who never knows what the hell he’s talking about.

Countless other acts of mostly state-sanctioned fascist violence later, here we are. Killing fascists in video games bears the weight of the political present. But we have to keep tradition alive, don’t we? And if games are going to give us fascists to kill, well, we’re going to have to kill them, aren’t we? And if I’m gonna kill fascists in a video game, I’m gonna do it as a meatpunk.

See, meatpunks have a particular way of going about this kind of thing. They drive meat-mechs that they refill at bloodstations in a world without a sun. They laugh together, cry together, get mad at each other and reconcile later on (more or less). And the meatpunks, as portrayed in Heather Flowers’ visual novel/mech brawler Extreme Meatpunks Forever, are queer as hell. There’s no hetero-masculine Captain America assembling the Avengers, here. This is a story about people who are brought together under terrible circumstances to overcome a world that’s stacked against them. They are trans and bi and nonbinary and lesbian and gay, and they are here to pilot their dripping flesh-robot mechs into punching some fash off some cliffs. They are messy and unpredictable and entirely not to be fucked with in any way whatsoever.

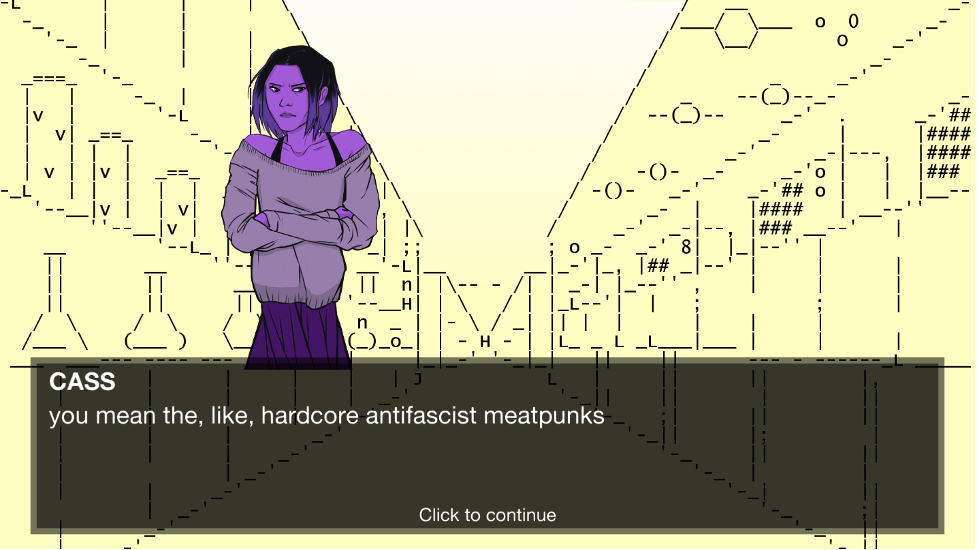

Sam, Cass, Brad, and Lianna are a group of mech pilots who live in a world populated by, as far as I can tell, two groups: antifascist meatpunks and fash. And one very confused youth pastor, who I don’t have time to get into here. (I haven’t played the second volume yet, so if there are more groups waiting in that one please don’t email us and spoil it for me!) Things get ugly outside the first meatpunk meeting, and a fight ensues in which the wrong fash is kicked off a cliff at the wrong time, and the whole crew finds themselves on the run. Most of this action takes place in a scrolling dialogue over colorful ASCII art, with the rest taking place inside one of the four mechs, each of which has a different set of fighting abilities. Mechs don’t die by taking damage on their own; the only way to kill one is to push it off a cliff. And push you will.

The game has seen criticism over its fighting mechanics, and I get it. It can be a little clunky, and don’t even think about trying to play it with a touchpad. But, come on. Half of the “punk” in meatpunk is the DIY aesthetic—the ASCII art, the surprising transitions between scenes, the sometimes-unexpected physics of a mech brawl. Punk isn’t made to be perfect. Punk is raw. And Extreme Meatpunks Forever is a sometimes brutally raw story about feeling like you don’t know what’s going on in the world or how to fix it, but you know that if you punch a fash’s lights out, you’ll feel better, at least for a little while.

The “meat” half is just as compelling. As Flowers describes in a document downloadable from itch.io called the “Meatpunk Manifesto”: “deal with viscerality in original ways. send everything to hell. make mechs out of meat. there’s a whole world of weird shit out there that we’ve barely scratched the surface of.” Under another heading (4: BODIES ARE WEIRD AND GROSS BUT ALSO COOL), the reader learns that “part of the meatpunk code is learning how to forge a positive relationship with your body.” And this is the meatiness that I find really compelling, all across this story. It’s not just about punching fascists. It’s about all the different kinds of embodiment—related to sex and gender, disability and race, and all the ways there are to exist—through which one can inhabit a world. A world, mind you, in which the fash are always lurking off somewhere, ready to say that only one kind of body is valuable, rejecting all others. Trust me, it’s that much more delicious when you kick their asses to hell.

Like our colleague Chris Breu said on Episode 2 of the Gamers with Glasses Show, the thing about “meat” in cyberpunk is that it’s usually the condition in which you would prefer not to find yourself. Extreme Meatpunks has cyberpunk dystopianism, robots, and body modification, but it does all of this in a meat-positive way, celebrating what it’s like to be a fleshy being in a world that wants you to conform to its boundaries and take away anything that makes you feel comfortable in your own skin. It’s a long-overdue approach to the cyberpunk video game, not unlike Samuel R. Delaney’s flesh-forward sci-fi epics. (For more critical reflection on the genre of cyberpunk, check out our primer on cyberpunk: “Technical and Crude.”)

There’s probably a lot more to be said about what it means to kill fascists in video games in a time when the attacker in the other mech could realistically be a family member, a co-worker, or one of those “good country people” I grew up with. But here’s what I know for now: I have been constantly angry for the last four years. Not once has it stopped. Even my greatest happinesses over the last few years have been marred by this raw edge of rage. And when I spend a few hours with the meatpunks, I can lean into that rage, lean into my body and whatever messy way it needs to be today, and use that meat to punch the shit out of a fascist.

For more excellent writing on the politics of bodies, read Nate’s piece on The Binding of Isaac and Chris Breu’s essay on Resident Evil. For other great indie punk games, check our indie cyberpunk series.