Nier: Automata and The Future of Planet Earth

Christian Haines, Managing Editor

NieR Automata – the 2017 surprise hit from Yoko Taro and Platinum Games – is known for a number of things: scantily-clad androids, a brilliant blend of shoot-em-up and hack-and-slash combat, and a complex narrative that requires multiple playthroughs to reach the true ending. It brings the weirdness of experimental indie games to the big budget fare of Square Enix. But the allure of Automata has as much to do with its natural scenes as its fast-paced action, sexy androids, and meta-narrative. The game sinks you into its environments. As you retread the same ground over and over, the landscape washing over you in earth tones, soft greens, and tranquil blues, you learn to appreciate a planet no longer under human control.

NieR: Automata is a post-Anthropocene game. The Anthropocene is an epoch in Earth’s deep history defined by the imprint of human civilization. It signals that human-caused climate change has made such an impact on the planet that every single ecosystem whispers (or screams) with human presence. The Anthropocene is catastrophic. It sings of extinction, of contamination and desecration. We know it not only through increasing temperatures but also through the proliferation of wildfires in California and Australia; rising sea waters submerging the coastal lines of continents; and the intensification of hurricanes and monsoons. But there is an irony of the Anthropocene, namely, that in compelling us to think about the planet on a geological scale, it also forces us to reckon with the possibility – the likelihood, even – of human extinction.

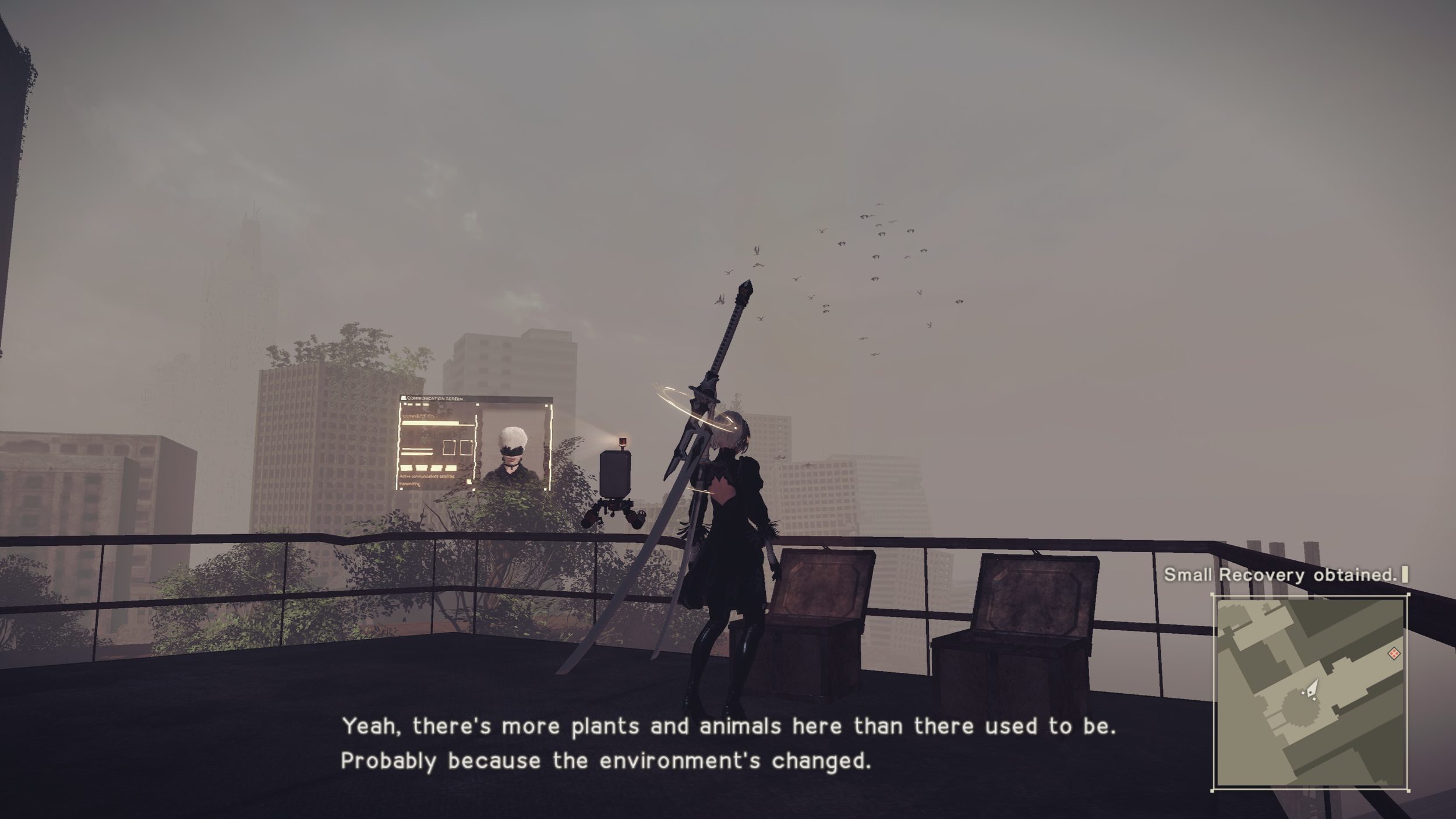

Automata is a post-Anthropocene game not only because humans have disappeared from the planet – you learn, in the second playthrough, that the humans for whom you’re supposedly fighting died off long ago – but also because enough time has passed that the Earth has rewilded itself. Moose and boars wander through the crumbling concrete remains of what once was a mall. The desert consumes a swing set in a public housing project. Waterfalls tumble out of the broken pipes of an urban sewer system. Wilderness has returned, not as the opposite of civilization but in the ruins of it. As 2B – the android protagonist of the first playthrough – exits the convoluted metalworks of a factory, a flock of birds flies across the screen. “Is that…?” 2B gasps in surprise. “You mean, the birds,” 9S – your companion android – replies. “Yeah, there’s more plants and animals than there used to be. Probably because the environment’s changed.” In this brief exchange, there’s the promise of environmental repair, the hope that time might heal the damage humans have inflicted on the planet.

It’s easy to overlook this moment. After all, minutes later you’re fighting a towering robotic boss with gigantic buzz saws for arms. Even if you successfully make it through this combat encounter, dodging at the right instants, hacking and slashing your way towards victory, the sequence ends with a cut scene in which 9S and 2B self-destruct in an effort to take out even more enemies. It’s a scene that speaks to the futility of war, the senselessness of trying to make meaning through destruction. Which is to say that it’s part of a broader set of philosophical ruminations on human nature, freedom, time, and extinction.

Although dramatic scenes punctuate Automata, most of the game consists of slower stretches of time. You wander from a desert wasteland to a forest kingdom, from the forest to an amusement park. These landscapes are often monotonous, but they’re still beautiful. The desert, for example, is a golden sea, dotted by the occasional stone formation and a lone oasis with a handful of trees and a watering hole. You can spend hours surfing its dunes without much happening. This slowness lends the game a meditative air, especially because it’s accompanied by Keiichi Okabe’s wonderful music. Songs such as “City Ruins (Rays of Light)” and “Vague Hope (Cold Rain)” drift in and out, the soft twinkle of piano keys blending with your steps as you collect resources or make your way towards another mission objective. Dreamy vocals, echoes of an extinct species, enter and exit the atmosphere, while string instruments carry the melody forward, ensuring that slowness never becomes stasis. Automata can be a boring game. It’s slow and repetitive. It’s not afraid to disable the fast travel system. But this is also its strength: it’s a game that lets your mind wander, though not without first introducing the seeds of thought.

There are, I think, two ways of reading these slower stretches of time. The first matches the popular interpretation of NieR: Automata as an existential meditation on what it means to be human. (For examples, see this article, and this one, and this one.)The slower moments encourage players to reflect on what makes a life meaningful, on how we reckon with the passage of time and the loss that goes along with it. Playing as an android only amplifies this existential bent. Not unlike Lieutenant Data in Star Trek: The Next Generation or Roy Batty in Blade Runner, the non-human character who resembles a human being turns out to be the most human of all. It’s only in trying to measure up to humanity, in not being able to take being human for granted, that an ethical existence can be achieved. The NPCs and enemies named after philosophers such as Sartre and Hegel are a nod in this direction. For all their differences, these are thinkers for whom human qualities like freedom or self-consciousness have to be earned through praxis, through action in the world. They aren’t a given.

The other interpretation might be called the posthuman reading. Instead of assuming that Automata affirms humanity, we might ask how it draws attention to the non-human elements of its environments and characters. We can measure 2B and 9S against how closely they match our human frameworks, but we might also note the ways that they escape these frameworks. 9S’s hacking mini-game – twin-stick shooting arenas simulating the digital brains of your enemies – doesn’t have an obvious analogy to human experience. A2’s beserk mode and the bullet time enabled by using the “Overclock” skill chip might be seen as superhuman, but they might also be read as something other than human – as technological abilities that mark the difference between androids and humans. Likewise, players can interpret the game’s environments in terms of what they meant to the humans who used to inhabit them, but they might also notice how the ruins of human civilization have given way to other kinds of life: to machines experimenting with new social systems, to trees as large as skyscrapers, to moose, birds, and boars who have forgotten whatever threat humans once posed.

When I find myself absorbed by the landscapes of Automata, I’m thinking less about what makes one human than about what this planet might look like thousands or millions of years in the future. Will polluted streams run clear? Will deforested hills brim with trees, ferns, and unrecognizable species? This is what I love about NieR: Automata: it transmutes despair over human fate into hope for the planet. It promises that the ruin of civilization might not mean apocalypse. (Automata is, I would argue, a post-post-apocalyptic game, less interested in how the world ends than in what might come next. This is part of why it’s so refreshing to gamers who’ve already experienced a dozen different flavors of apocalypse.) In this light, our anxiety over death and the meaninglessness of existence might lead to something besides human freedom or self-consciousness. It might leads to the recognition that our planet has a history and that – with or without us – something wild might yet appear.

For more articles on games and the environment, read Nate Schmidt’s introduction to our “Green Screens” series (of which this article is a part) and Alenda Y. Chang and Ed Chang on “10 Games to Play for Earth Day.”