The Lonely Post-Industrial Wilderness in The Last of Us Part 2

Roger Whitson, Managing Editor

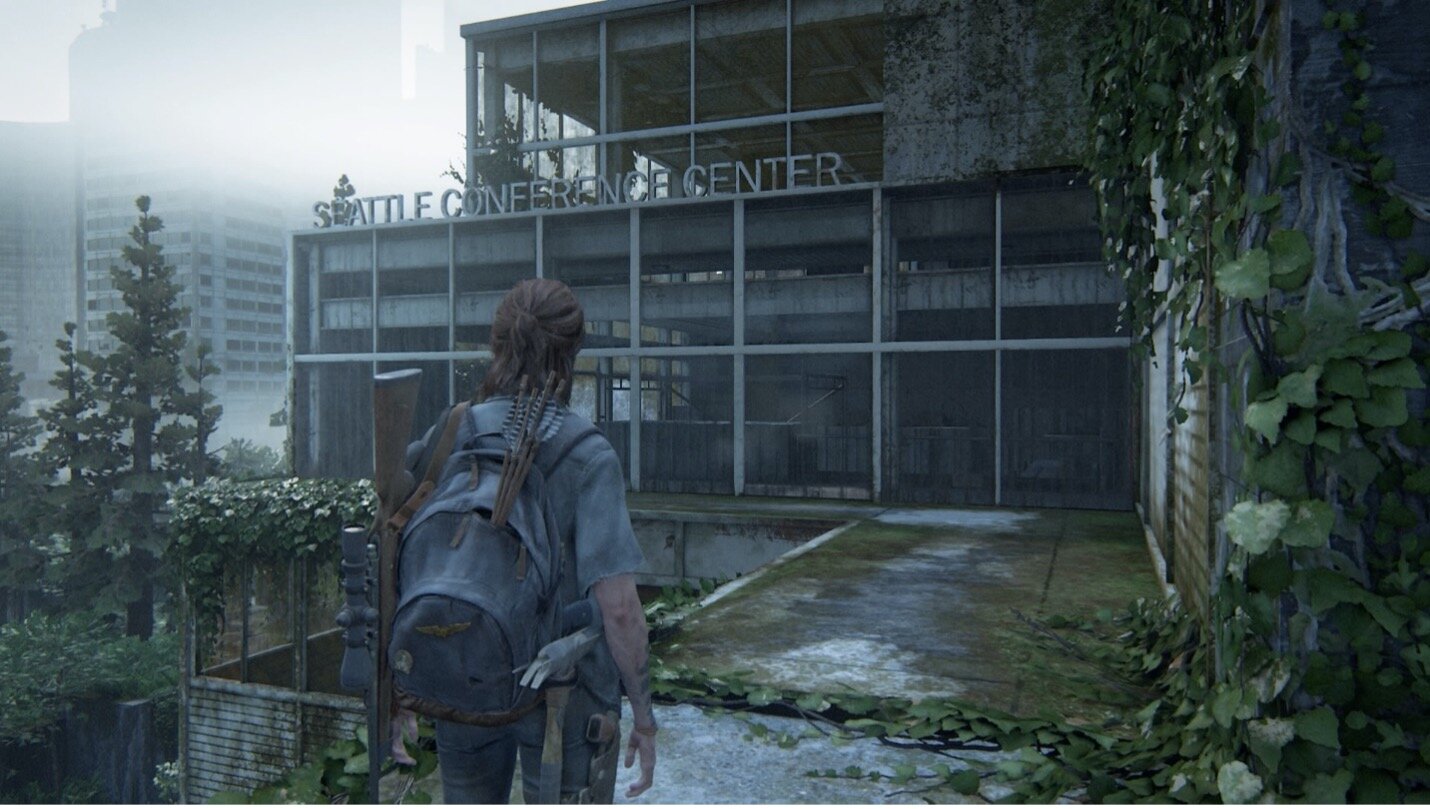

I played The Last of Us Part 2 during the one-year anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic, and I found myself exploring an overgrown location called “The Seattle Convention Center.” This was chilling because I had attended a conference at “The Washington State Convention Center,” the real-world location serving as the basis of that game space, a few months before the first lockdown. In-game, I crawled through one of the many broken windows and noted, with further alarm, that the furniture, stairs, and carpet were apparently identical to the building I walked through in January 2020. The strange resonances recalled my anxious fantasies during the early months of the pandemic: my fear as I pondered the destruction of supply lines, my loneliness as I lived alone in a basement apartment in Idaho, my alarm as old friends bought up firearms to protect their children from vandals. The Last of Us Part 2 had changed my memories of the time before the pandemic into what Jessie Oak Taylor has called a “post-industrial wilderness,” a wilderness landscape that reflects the sense of loss and death involved in a horrible cataclysm. These wildernesses mix ecological reclamation with overturned human infrastructure, turning the wilderness into an uncanny meditation on human loss.

Crawling through the ruins of Seattle as Ellie, I couldn’t help but think of Richard Jefferies’s 1885 novel After London; or Wild England. The first chapter describes London being reclaimed by nature after an unexplained apocalypse: “[i]t became green everywhere in the first spring, after London ended, so that all in the country looked alike.” Jefferies narrates arable fields overrun by couch-grass, footpaths concealed by grasses sprung up and not cut away, and former fields destroyed by “thorns, briars, brambles, and saplings.” No human characters appear at all in the first chapter, and in their absence, Jefferies focuses on the movement of animals and plants. Piles of trees and branches are turned into “battering rams [that] cracked and split the bridges of solid stone which the ancients had built. These and the iron bridges likewise were overthrown, and presently quite disappeared, for the very foundations were covered with the sand and gravel silted up.” Jefferies pans back, taking us to a vision of London “from an elevation [in which] there was nothing visible but endless forest and marsh.”

Taylor derives his theory of the post-industrial wilderness from Jefferies’s novel: “the human is present in these opening chapters only as palpable absence.” He also aligns the lush botanical description of After London with the speculative natural history found in Alan Weisman’s The World Without Us, in which we’re asked to imagine what would happen if human beings suddenly disappeared and nature reclaimed the earth. In the first chapter of After London, ecological processes actively annihilate the fields and domesticated animals left behind as traces of human culture.

Post-industrial wildernesses are haunted wildernesses, existing not in and of themselves but as traces of our absence. They eerily reflect the abandoned highways, empty city squares, and closed restaurant fronts whose landscapes were a staple of the early months of the pandemic. The six-minute video for Jessie Ware’s “Remember Where You Are” captures the human absence of COVID0-19 beautifully as actor Gemma Arterton roams the empty streets of London during lockdown. The smooth layering of Ware’s voice accompanied by her signature disco-inspired pop music suggests the ghost of a dance party. The music also lends a false optimism that is harshly undercut by Arterton’s tearful face, yet reinforced ever so slightly when she mouths a line from the chorus or slightly smiles. Lit storefronts and apartment complexes make the streets look simultaneously alive and, paradoxically, filled with a haunting absence.

The Last of Us, Part 2 is filled with post-industrial wilderness. As Taylor says of After London and The World Without Us, it is easy at times to forget the human plots of the game and focus instead on the vibrant, thriving flora surrounding the characters as they make their way across the post-pandemic apocalypse. Once-teeming suburbs are overgrown with vines, their roots ripping apart foundations. We find that the zombie infection is carried by spores which infect brains and mutate human bodies beyond all recognition. The spores also contribute to the fungal overgrowth in the corners of ruined buildings explored throughout the game. The ecologies that persist are like cemeteries of human experience, with high rises like gravestones whose names have long since vanished. While exploring the abandoned ICU of Seattle hospital, Abbie comes across an eerie note from Kayla Higashi written in the early days of the game’s zombie pandemic. In a tone reminiscent of the doctors and nurses experiencing trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic, Higashi says she’s worried she’s going to have a mental breakdown. “I’ve seen what the patients turn into. Every single adult and child that is brought in here with a bite or scratch is going to lose their minds and we keep lying to them.” We never learn what happens to Higashi, though her patients are to be encountered in the clickers and stalkers wandering through the halls.

Toward the end of After London, the character Felix encounters a polluted lake filled with a thick, black, rusty sludge with “an offensive odor.” Felix continues: “[t]he odor clung to his hand, and he could not remove it, to his great disgust. It was like nothing he had ever smelt before, and not in the least like the vapour of marshes.” It is a thick, poisonous lake — one whose sticky consistency threatens to destroy his canoe and leave him stranded. As he explores the blighted landscape, he comes across what looks like a skeleton but then is revealed to be “merely the impression of one, the actual bones had long since disappeared.” Then, even more alarmingly, he finds “three or four more, intertangled and superimposed as if the unhappy beings had fallen partly across each other, and in that position had mouldered away leaving nothing but their outline.” From the palpable absence of what was mistaken to be a human skeleton, we turn to the remains of a dehumanized chimera formed from the now entangled and unrecognizable shapes of bodies piled on top of one another.

The Last of Us, Part 2 has its own dehumanized chimera, found when Abbie explores the basement of Seattle Hospital’s ICU. It is named the “Rat King”: a superorganism formed from the conjoined bodies of infected altered by decades of exposure to fungal spores. The name comes from medieval reports of rats whose tails had somehow become conjoined. The creature gives a new perspective to the post-industrial wildernesses found in the game: instead of the traces of human bodies lost to ecological processes, it is the body itself that has become so mutated and disfigured as to become unrecognizable as a human.

Viruses and fungal spores mutate the human body beyond recognition in The Last of Us, turning it into yet another blank gravestone of humanity. Just as nature reclaims urban landscapes while emptying them of human beings and human connection, the Rat King is a grotesque parody of this longing for connection. Bodies are very much connected in the Rat King, but it is a connection formed of mutation — bodies conjoined together with spores and slime with little recognition of the loss that’s the hallmark of post-industrial landscapes. In fact, the Rat King is the only community possible among the infected. All of the other zombies in the game wander listlessly until you aggravate them. They are barely aware of one another at all.

Image from The Last of Us Wiki, https://thelastofus.fandom.com/wiki/Rat_King.

The desperation with which you confront the Rat King as Abbie in The Last of Us Part 2 reflects the loneliness of those early months in lockdown. COVID-19 exploited our human communities, turning us into vectors for infection and forcing us into isolation. Abby is completely alone in the dark water-logged basement of Seattle Hospital, with only the remnants of Higashi’s mutated patients to keep her company. There is no human community here, only viral contagion. We are not so far from the toxic sludge Felix encounters in After London as the ultimate by-product of the post-industrial wasteland. My darkest reflection of the past year comes in the realization that the very thing I’ve longed for is what has betrayed me: human community. I feel this betrayal each and every time I come across someone who refuses to wear a mask or someone who, instead of getting vaccinated, drowns themselves and their loved ones in a sea of conspiracy theory.

Speculative natural historians like Weisman celebrate the post-industrial wilderness as a utopia without humans, suggesting that nature is better off without us. The Last of Us Part 2 and After London underscore the emptiness of this vision of human absence. They also repudiate the possibility of collective action against death and disease, suggesting that such efforts will ultimately be overcome by tribalism. After failing at multiple attempts to kill Abby, Ellie abandons her family and murders most of Abby’s friends in her seemingly endless quest to take revenge for the murder of Joel. The final scene finds her alone, in an empty house, playing the guitar Joel gifts her at the beginning of the game. Likewise, celebrations at the rollout of the vaccine are harshly contrasted with the “tsunami of deaths” occurring during India’s most recent wave of COVID-19. For every conservative politician insisting that we return to normal, we can see pictures of cremated remains that will never experience normal again. Instead of the abandoned highways and other post-industrial images that dominated our imagination in the first months of the pandemic as heralding an end to global capitalism and its numerous oppressions, we’re simply left with our ongoing, violent, tribal attempts to survive — and the countless examples of those who did not.

Further reading:

Jesse Oak Taylor, “The Novel after Nature, Nature after the Novel: Richard Jefferies’s Post-Anthropocene Romance,” https://muse.jhu.edu/article/687649/pdf.